Guido da Viegevano

Today, a medieval inventor goes to war -- almost. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

It's pretty clear that war has been a poor incentive to developing new technology. But human ingenuity does often use war as an excuse. One marvelous example comes out of the dog days of the High Middle Ages.

During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Europe directed remarkable energy into mills, cathedrals, book-making -- technologies that were both liberating and civilizing. Then Europe began diverting its energy. The early crusades had reopened pilgrim travel to Jerusalem. They'd created an East-West commerce of goods and ideas. At the outset, both the Arabic and the European worlds had the strength of religious tolerance and open-mindedness.

But the crusades led both sides to trade all that for the most self-destructive prejudice and hatred. As the Hundred Years War began in 1337, fragmentary crusades were still being mounted, though the Moslems were finally driving Europeans out of the Holy Land.

After that, a dyspeptic Europe turned its bile on itself. A generation of bad weather, failed crops, famine and susceptibility to disease had decimated the population. The plague finally arrived ten years into the Hundred Years War, and before it was done, half the European population had died.

Two years before the Hundred Years War, a physician and engineer named Guido da Vigevano attached himself to Philippe VI of France, whom he expected to go on an obligatory crusade. To strengthen his position with Philippe, Guido wrote a sort of crusade handbook for him. Nine folios of the book advise the king on how to look after his health on the journey. The other fourteen folios advise him on military technology.

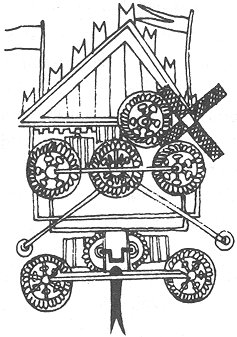

Historian Rupert Hall points out muddy inconsistencies between Guido's text and sketches. But the machines are clear enough in their broad intent. They are a last breath of the soaring medieval imagination. Guido knew wood was hard to find in the Holy Land, so his siege equipment was to be broken into prefabricated parts that horses could carry. He said a lot about joints and assembly. We find folding attack boats and pontoon bridges -- innovative new forms of body armor. We find two self-propelled battle wagons: one was crank-driven; the other carried its own windmill for power.

King Philippe never got to the Holy Land. No one ever tried to build Guido's wonderful machinery. Two years later it was King Philippe who started the Hundred Years War by seizing an English-held duchy in southwestern France.

So I look at Guido's marvelous Picasso-like sketches, without perspective or three-dimensionality -- ideas tumbling one over the other. It was a kind of fantasy armory for beating back a fantasy enemy. It was a child's' view of war, remote from the practical world outside. It was so very far from a world bent on setting loose the ancient and straightforward technologies of anger.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Hall. A. R., Guido's Texaurus, 1335. Humana Civilitas: Sources and Studies Relating to the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, Vol 1, On Pre-Modern Technology and Science, A Volume of Studies in Honor of Lynn White, Jr. (Bert S. Hall and Delno C. West, eds.). Malibu, CA: Undena Publications, 1976, pp. 10-52.

This is a greatly updated version of Episode 115.

One of Guido da Vigevano's windmill-powered vehicles