The Double-Bitted Axe

Today, we learn to use a new axe. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

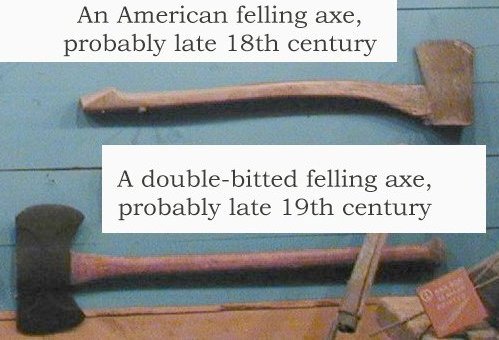

A new kind of felling axe arose in late Colonial America. It was the familiar axe with a gracefully curved handle and a head counter-weighted on the side opposite the blade. It was quite different from the European axe with its straight handle fixed to the back of a long narrow blade. For better or worse, the new axe converted our forests to farmlands. It transformed the new continent.

But European critics distrusted it. It took extra skill to wield it because it used new principles of balance. Still, by the time of the 1851 Crystal Palace exhibition, axe heads were turning up as primary American trade goods. When English makers copied them, they stamped their imitations with American makers' names.

Such an axe could come into being because American workers were free of any canon of established technology. Our early craftsmen took great pride in experimenting, and it often paid off handsomely.

So it should be no surprise that our craftsmen invented a second radical axe-head design about the time of the Civil War -- the double-bitted axe. Lumbering became a major Northern industry, and mythical Paul Bunyan arose to represent it. Armed with this new axe, Bunyan was the prototypical lumberjack. He was woodcutting carried to a new level -- deforesting America from Maine to Minnesota.

Historian Ronald Jager tells the story of Bunyan's new double-bitted axe. It was symmetrical about the handle with wide blades on either side. You and I have seen them, but out of the corner of our eye. The U.S. Post Office got it wrong when they issued a Paul Bunyan stamp. They showed him carrying the old counterbalanced axe. The Boy Scouts award a Paul Bunyan Woodsman emblem that properly shows a double-bitted axe and nothing else.

But this new axe required new skills, while it also provided a new cutting efficiency. Its aerodynamics are such that, if you know how to swing it cleanly, it offers hardly any drag. Let it catch the wind just a little, and it can be dangerously unstable.

The Northern lumberjacks, this new breed of skilled workers, kept one side of their axe sharp and let the other be nicked and blunted. The sharp blade was for cutting cleanly into wood. If they saw anything dubious, like a tough knot, they'd rotate the handle and use the rough blade.

European experts again looked at the new American axe and again declared it awkward. But this time they didn't change their minds. Nor did the new axe travel very far west of Minnesota. While Paul Bunyan, with his double-bitted axe, became an important chapter in the history of the axe, the chapter was an isolated one.

The history of the axe is the history of America. Henry David Thoreau caught America's long love affair with the axe when he wrote about borrowing one during his stay by Walden Pond. He said,

The owner of the axe, as he released his hold on it,

said that it was the apple of his eye;

but I returned it sharper than I received it.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Jager, R., Tool and Symbol: The Success of the Double-Bitted Axe in North America. Technology and Culture, Vol. 40, No. 4, October 1999, pp. 833-860.

Early American hatchets, still similar to their European forebears. (from the Sloane Stanley Museum, Kent, CT.)

(photo by John Lienhard)

Sloane Stanley Museum, Kent, CT

(photo by John Lienhard)

The Boy Scout's Paul Bunyan Woodsman's Emblem