Photography: The Salad Days

Today, where was photography headed in 1854? The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The 1854 Cyclopaedia of Useful Arts has a long article on photography. That was less than a decade after Daguerre worked the kinks out of his process and gave us the first practical photography. Now here are thirteen two-column pages on this new technology.

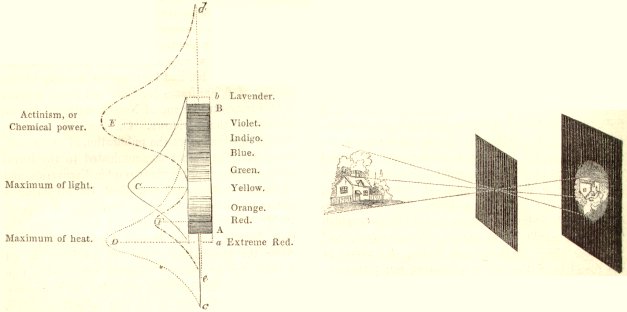

Not all of this was new. The ancients built an aid to artists called a camera obscura. A hole in one wall of a dark room casts a sharp image, upside down, on the opposite wall. That's how our cameras work, but we have some kind of light-responsive material (like film) on the far wall to capture the image. Sixteenth-century inventors equipped their camera obscuras with lenses that sharpened the pictures.

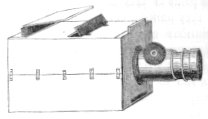

But not till the 1830s could we take pictures -- that is, take them away from the camera without first tracing them out. When this article was written, you still couldn't go to the store to buy film or even a complete camera. Here's a vast user's manual for assembling a camera and preparing plates that'll carry pictures away.

But not till the 1830s could we take pictures -- that is, take them away from the camera without first tracing them out. When this article was written, you still couldn't go to the store to buy film or even a complete camera. Here's a vast user's manual for assembling a camera and preparing plates that'll carry pictures away.

It reminds me of articles on computers before software appeared, twenty years ago. Integrated circuits were then no older than these embryonic cameras. In the late 1970s we had to write our own programs, just as we had to make our own "film" in 1854.

So this article gives us a chemistry tutorial. It tells of nitrate of potash, iodide of potassium, collodion, hyposulphite of soda, albumen, and pyrogallic acid. But beneath all that process chemistry rises another question: "What will photography be in our lives?" Is it to be a fine art or a useful art?

The Crystal Palace Exhibition had just laid out the tapestry of mid-19th-century art and technology, and it'd presented photography as art. The article looks for greater emphasis on natural history -- images of dissected plants and animals. Wouldn't a more scientific view of the new art have produced color photography? Color was feasible in principle; why hadn't it been invented yet?

A quotation in the article says, "Photography holds a place at present intermediate between an art and a science." It could go either way. Of course, captured images are now so pervasive that the issue loses all meaning. Every corner of art, technology, science, and entertainment teems with captured images.

By century's end, the Impressionists reacted to the literal eye of the camera by trying to capture the impression beyond the image. One typical commentator spoke of the supposed sterility of cameras when he compared a live speech with "the colourless photography of a printed record." Art and technology seemed to be on a collision course, but they were actually fusing into a single enterprise. It finally took artists like Alfred Stieglitz to show how far from simple reporting the camera lens would go. Perhaps the greatest surprise in the evolution of the camera is exactly how far from literal truth it has eventually taken us.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

PHOTOGRAPHY. Cyclopaedia of Useful Arts (Charles Tomlinson, ed.) Vol. II, Part I, London: George Virtue & Co., 1854. pp. 393-405.