Paper in Samarkand

Today, paper makes a long journey. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

A word to consider next time you open a new ream of shiny white paper is the Arabic word rizmah. It means a bale or a bundle. The Spanish made rizmah into resma, and the French made reyme of it. It finally became the English word ream -- a bundle of twenty quires (or 500 sheets) of paper. That word-trail matches the trail of paper almost perfectly as it moved from the east to the west.

The Chinese invented paper in 49 BC. They began using it as a writing material in AD 105. By the seventh century, the use of paper had spread east to Japan and west to Samarkand.

That was just after Islam had begun spreading outward from the mid-East. Paper and Islam converged when Arab forces reached Samarkand, where paper had been in use for just two generations. Under Arab rule, Samarkand became a paper-making center.

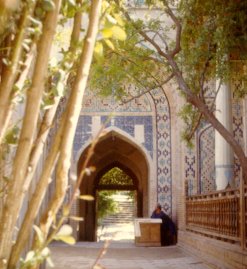

All paper is made of plant fibers of one sort or another, and Samarkand paper was made of mulberry fiber. Two recollections linger with me after my visit to Samarkand years ago. They are the beautiful mosques and air heavy with the smell of mulberry.

All paper is made of plant fibers of one sort or another, and Samarkand paper was made of mulberry fiber. Two recollections linger with me after my visit to Samarkand years ago. They are the beautiful mosques and air heavy with the smell of mulberry.

The Arabs also made paper centers of Baghdad and Damascus. The intellectual center of the world had, for a long time, been the city of Alexandria at the mouth of the papyrus-rich Nile Delta.

Pergamon, in western Turkey, had become a parchment-based intellectual center, and parchment would become Europe's writing material. But, in the 8th century, intellectual ascendancy passed to Baghdad, and it came to rest on the new writing medium of paper.

Historian Jonathan Bloom drives home the importance of that fact. Before we had cheap and abundant paper, arithmetic involved erasing and shifting numbers -- operations that could be done on slate, but not paper. In AD 952, Arab mathematician al-Uqlidisi used Indian algorithms to create neat once-through methods that could be done on paper. Paper drove the creation of our methods for doing multiplication and long division.

The use of paper slowly crept westward. Cairo was making paper by the 10th century, Tunisia and Islamic Spain by the 11th. Paper didn't cross the Pyrenees into Europe. Rather, it entered by way of Islamic Sicily. It was being made in Italy by 1268.

Both Hebrew and Islamic scripture had first been put on parchment. Both religions were reluctant to put scripture on anything so modest as paper, despite its strength and durability. The flow of paper into Europe was also slowed by Christians, who called it an infidel technology. Central Europe didn't take up paper until the 14th century, and England only at the end of the 15th.

Not until 1578 did paper reach Russia after its long looping trip from China, through Samarkand, into the Holy Land, across North Africa, up into Europe and finally to Moscow. But the great nexus in this glacial migration of paper was Samarkand -- ancient, sunlit, and sweetly perfumed with the delicate smell of mulberry.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Bloom, J. M., Revolution by the Ream: A History of Paper. Aramco World, May/June 1999, pp. 26-39. (See also a more recent book-length account: Bloom, J. M., The History and Impact of Paper in the Islamic Lands New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001.)