Eighteenth-Century Factory Maintenance

Today, a question of image and reality. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Years ago a librarian showed me a 15th-century copy of a book by Aristotle, one of the first books ever printed in Greek. "They say this is one of the great early printed books," she said. But then she added, "Look at it, it's perfect -- no tears, no grease from handling. It's the same with every copy I've ever seen. This is supposed to be one of the most important books, and no one's ever read it." She was right, of course. Can anything be as sterile as an old book that carries no marks of use!

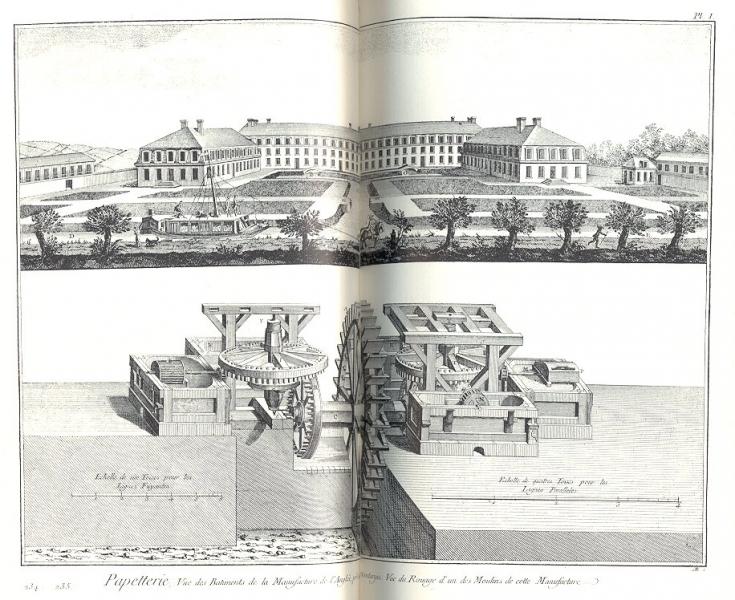

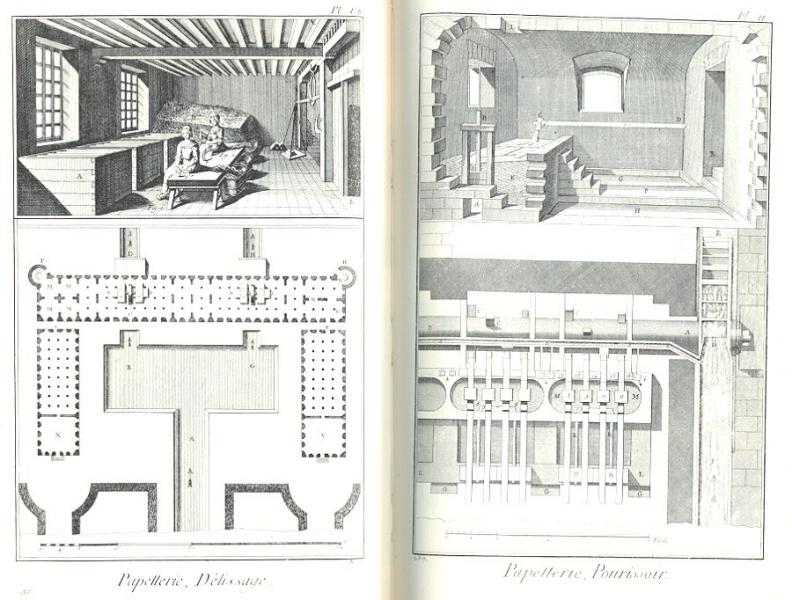

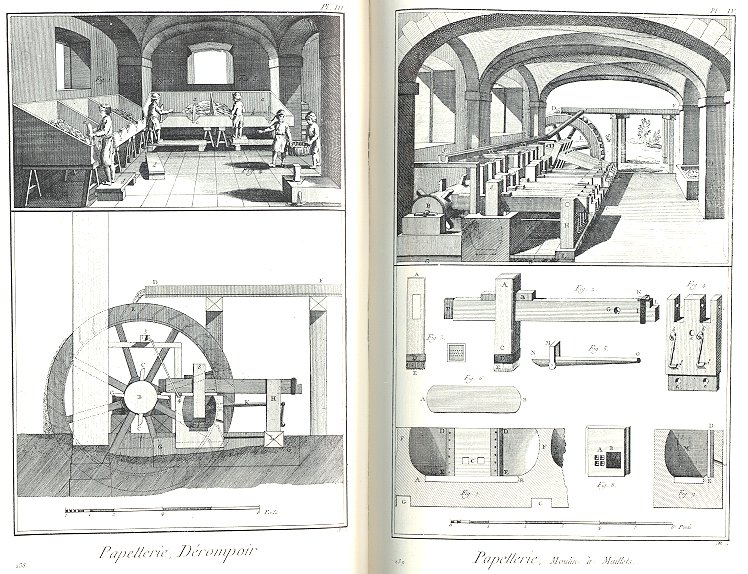

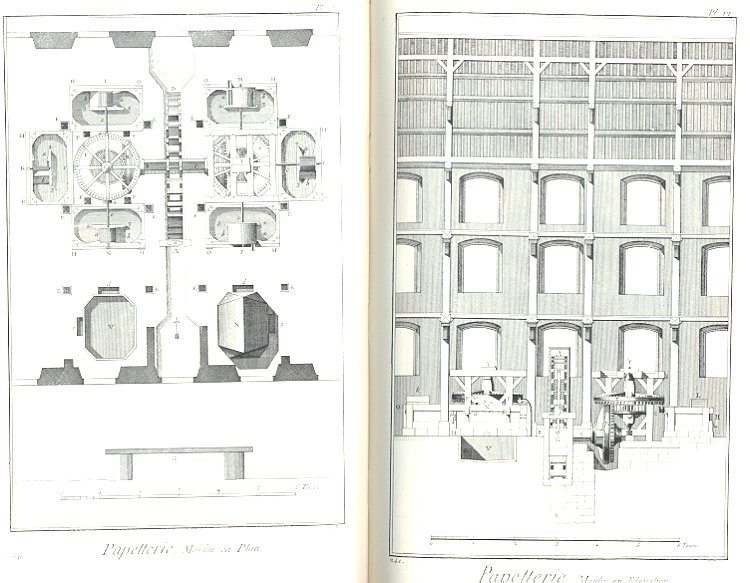

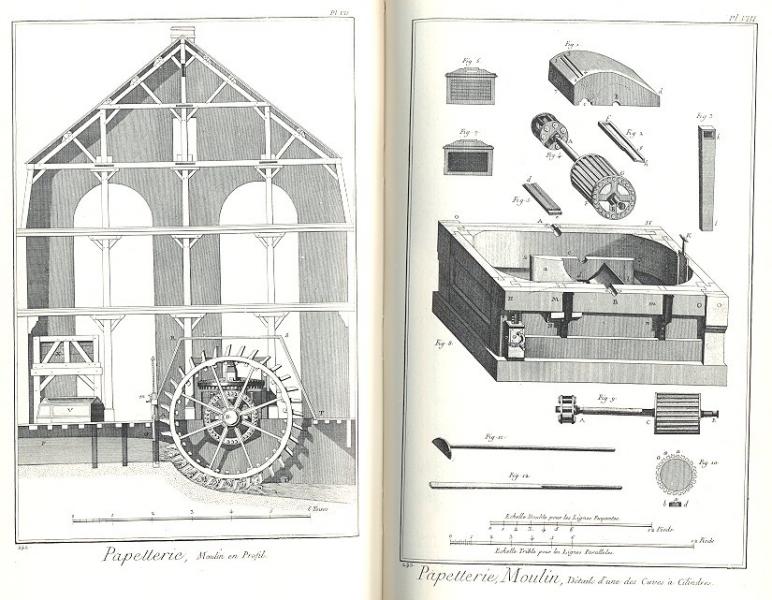

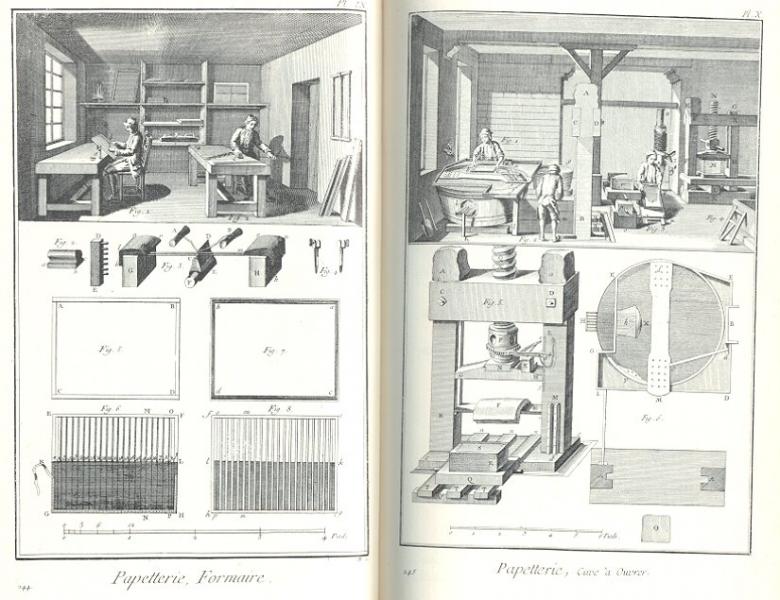

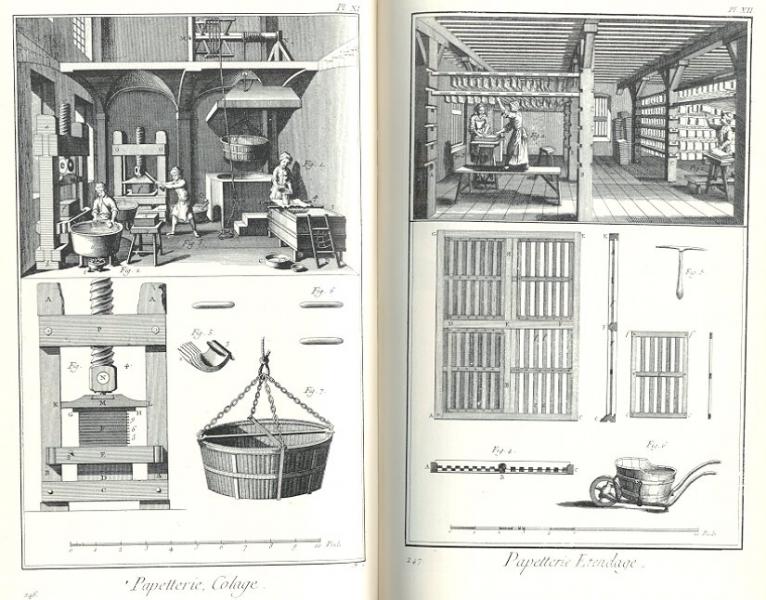

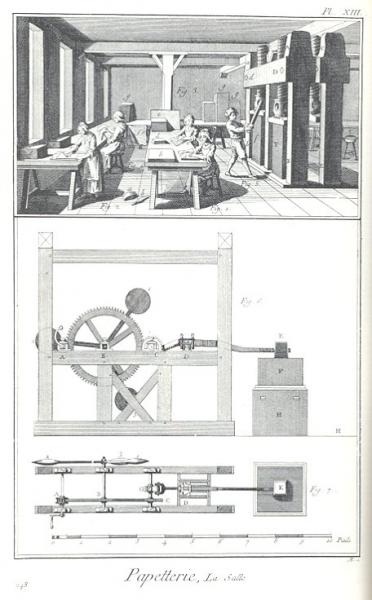

Now historian Pierre Claude Reynard offers another such case. He looks at maintenance in late-18th-century paper mills. France was then the major producer of paper. Much of what we know about the industry comes from Diderot's Dictionary of the Arts and Trades. You've all seen prints from Diderot's monumental work. He describes the early trades: baking, printing, weaving, and, of course, paper making. All these works are shown as clean and uncluttered. The shops are spacious and orderly. Diderot's pictures of paper-making show that same clean perfection.

But Reynard goes into old records of the French paper-making industry, and what he finds doesn't look at all like Diderot. Factory upkeep involved almost none of what we'd call maintenance. Most equipment was built of wood, and it had a life of only five or ten years. The trick was to build a new piece of equipment, run it until it wore out, then replace it. Since accounting practice ignored the loss of productivity as equipment aged and deteriorated, the actual shops functioned at some level of chaos.

The paper industry's troubles mounted as literacy and the demand for good paper rocketed up. That came home to me when I saw a copy of William Billings's Colonial songbook at Yale. Billings, who strongly supported American independence, delayed publication until he could print the book on American-made paper. It's terrible gray and grainy stuff. No one but Billings would've chosen it.

Still, France clung to her run-to-failure policies while equipment grew ever more sophisticated. The Montgolfier Brothers, whose main work was not flying balloons but developing cutting-edge paper-making equipment, developed a new beater for pounding rags into pulp. It demanded a whole new level of maintenance skill. Only in the long run did such machines force new modes of factory operation and new methods of accounting to go with them.

So Diderot's lovely encyclopaedia of industrial practice, like that clean medieval volume of Aristotle, was only an icon. It was revolutionary propaganda more than a working document. Diderot's idealized images celebrated The Worker much as the art of Stalin did, 150 years later. And we need to remind ourselves that we find our way to the truth of history only when we locate the messiness that has to underlie all we do.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Reynard, P. C., Unreliable Mills: Maintenance Practices in Early Modern Papermaking. Technology and Culture, Vol. 40, No. 2, April 1999, pp. 237-262.

For more on the Diderot Encyclopedia, see Episode 122.

Below are a set of thumbnails of all the Diderot images of papermaking. These were obtained from Diderot, D., Diderot Encyclopedia: The Complete Illustrations. New York: Abrams, 1978, provided by the UH Art and Architecture Library. Click on the thumbnail to see a large image.