Record Setting

Today, we come to an end of record-setting. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Records are funny things. Take the speed of flight: in 1880, the first primitive airships went about seven miles an hour. WW-I airplanes reached 130 miles an hour. 1930s racing planes reached 300, and in 1944 German combat jets flew almost 600 miles an hour -- just this side of the sound barrier. We'd been doubling airspeeds every nine years, and we kept right on going. By 1967, the North American X-15A reached more than 4000 miles an hour.

Then a strange thing happened. We launched our first satellites in 1957, and we put a live person in one in 1961. Suddenly, people were reaching 26,000 miles an hour. Once clear of Earth's atmosphere, we could go almost any speed we wanted. Suddenly, no one gave a fig about speed records any more. Henceforth, the big problem would no longer be speed, but launching and landing.

When the search for high speeds stopped being fun, we had to look for some other kind of record. Try the duration of terrestrial flight. In 1903 the Wright brothers stayed up for 12 seconds. Five years later they were first to stay aloft more than an hour. In 1914 a German plane stayed up for over 24 hours. And Lindbergh took 33 hours for his transatlantic flight in 1927.

Of course, the real drive was for long distances -- not just staying up a long time. The goal that got away from us for years was a non-stop round-the-world flight with no refueling. That's something we didn't manage until 1986.

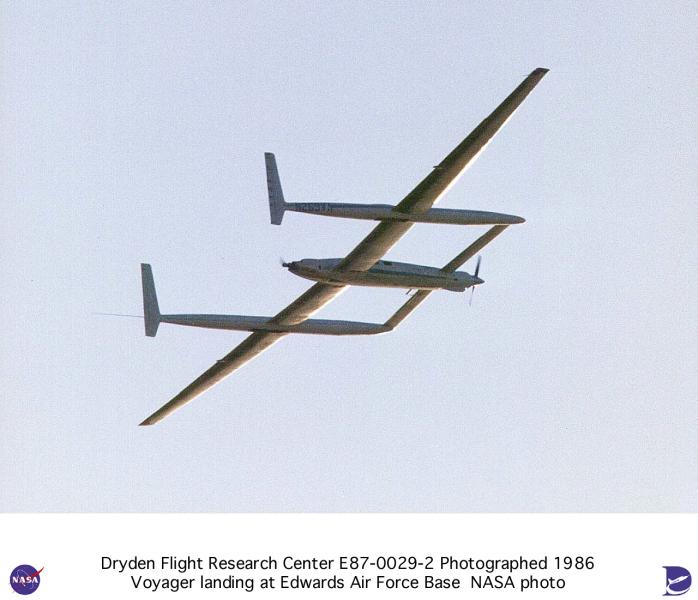

Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager flew their dainty experimental airplane Voyager around the world, setting both distance and endurance records. They stayed in the air nine days and did so before anyone accomplished the centuries-old hope of ballooning around the world. The Brietling Orbiter 3 balloon finally landed safely in Egypt in March 1999, after a nineteen-day trip around the world.

But two things were already undercutting both those records. For decades, the Air Force had been able to indefinitely refuel B-52 bombers in flight. Then, during the 1980s, the Canadian Research Council funded work on an airplane powered by microwave beams from stations on the earth. This unmanned airplane was also designed to stay up indefinitely. It was called SHARP, an acronym standing for Sustained High Altitude Relay Platform.

SHARP's longest flight before funding ran out was only 95 minutes, but the point was made. One of the developers said modestly, "The Wright brothers' first flight was 12 seconds. I think we'll do much better than that." Duration was clearly no longer an issue.

Records are such strange things. We chase one until we get better than the game we're playing. We play the game until we outgrow it; then we go off to a new game. But don't think I'm being cynical here. The payoff is often enormous. These games really are worth the candle.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Lienhard, J H., Rate of Technological Improvement Before and After the 1830's. Technology and Culture, Vol. 20, No. 3, 1979. pp. 515-530.

Lienhard, J. H., Some Ideas about Growth and Quality in Technology. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Vol. 27, 1985, pp. 265-281.

For more on the round-round-the-world flight of Voyager, see Episode 218.

For more on the Swiss/English flight of the Breitling Orbiter 3 flight around the world, see the website:

Wikipedia article about Voyager/

For a subsequent development along the lines of SHARP see Episode 1639.

This is a greatly revised version of old Episode 66.