Systems, Complexity, and Simplicity

Today, let's see what happens when our technologies join forces. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

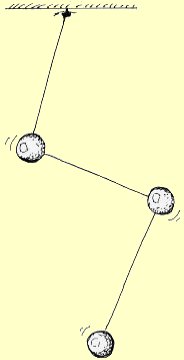

I ask you to try a little experiment when you have a moment. First find three metal masses -- nuts, bolts, lead sinkers -- whatever's handy. Hang one on the end of a thread and swing it. It forms a simple pendulum moving back and forth, or maybe describing a circle or a figure eight. Next, take a longer length of thread and attach all three masses along it -- maybe two feet apart. Then hang the string of masses from the ceiling. Start this system swinging and watch what happens. No matter how they start out, the weights are soon moving in completely unexpected ways.

The middle one might momentarily stop dead while the other two gyrate around it. They might all move in the same plane, or they might swing in circles. The movements keep changing. When we go from one mass to a system of three masses, we pass from a complex, but mathematically tractable motion, to motion that baffles us.

Our technological systems are like that. Do you remember October 1987, when a computer-controlled stock market responded to a ripple in the economy? We'd told our computers how to respond to certain market changes, but we were completely unprepared for their aggregate response. We were stunned when they flocked together and created the greatest one-day stock market crash the world had ever seen. That same complexity lay behind the Three Mile Island reactor failure. So many elements of the reactor were interconnected that no operator could diagnose trouble quickly enough. No one knew how to correct the situation instead of making it worse.

Yet complex systems are shot through our world today. A friend, a systems designer, made the point when he came back from Europe. "John," he said, "I had a remarkable experience in London. I had to call home, so I picked up the phone in my hotel, pushed a few buttons, and found myself talking to my wife in America."

I looked at him and said, "Yeah, So what?" He grinned and said, "Stop and think what it took to do that -- space technology to put up a satellite, electronic technologies on the ground, radio technologies in the sky, hotel management systems ..."

"Okay, okay," I cried. Of course he was scolding me for growing blasé. We depend everywhere on complexities that outrun our ability to see them whole. The corollary is that today's engineers have to spend far more time in the problems of combining elements effectively than they spend inventing them in the first place.

Ill-conceived systems threaten us with terrible mischief. Yet well-combined technologies offer amazing benefits and conveniences. We've reached that point in modern engineering, in modern medicine, even in the social dynamics of our huge populations. Work on any of these problems in isolation, when the pieces are all interrelated, and we'll create mischief rather than solutions. Forget the interconnection, and we'll be looking at three metal weights on a string -- spinning and whirling in mad and incomprehensible ways.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

This is a greatly revised version of old Episode 63.