Decisiveness

Today, let's not decide. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

We all agree that it's good to be decisive. To decide is to be strong. Indecision is weakness. Without decisions, the world will grind to a halt, won't it? Besides, we all need closure. I know I crave resolution the way I crave water when I'm thirsty.

Thomas Kuhn's book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, casts light on all this. To explain how scientific change takes place, he describes an experiment where subjects were allowed to see playing cards for a split second. Some people identified a card in a blink; some took a little longer. And here the fun begins:

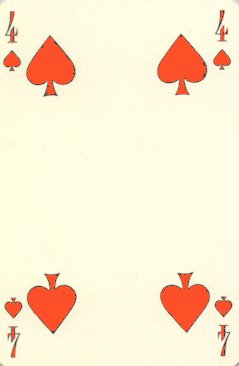

Among the cards were a few anomalies - like a red four of spades. The subjects identified those cards just as quickly as the familiar ones. They'd see a red four of spades and call it a four of hearts. They made a decision and moved on to the next card. When the exposure time was extended, some people saw what was going on and changed their minds. Others stayed committed to their decision and clung to it even after forty times the original exposure - even after they'd begun feeling acute distress.

The change of a scientific viewpoint works that way. Some people adjusted to the fact of evolution. Others clung to their decision that we'd been created without reference to the other animals. They couldn't believe they'd actually seen a red four of spades. It was the same story during the quantum revolution, the death of the caloric theory, and the new atomic theory. People who couldn't be indecisive never made the shift.

The problem grows even larger when we try to invent. Invention is destroyed by decisiveness. The moment I draw a line under a concept -- the moment I close off possibility -- I lose the option of seeing a better way to build my mousetrap. Years ago, a wise design engineer took me under his wing and mentored me. "Do a first design, then attack it," he said. "At first it'll be complex. It'll always work better as you change your mind and keep peeling away complication - as you keep relinquishing ideas."

Eventually, of course, we must give our drawings to the machine shop. But that closure had better be made grudgingly, because there's always a better way than we've thought of.

The fact is, we never need to make decisions. What we need to do is to take action. But that's not the same thing at all. A house is burning, and a child is trapped. We inform ourselves as best we can. Then we choose either to break in a window or to enter by the door. We don't decide; we act, because time grants no further choices. We leave decisions to Monday-morning quarterbacks.

There's always a better way, a better solution. We act, we make choices. But leave decisions to people who need the psychological comfort they provide. The only real closure we'll ever get is death. The glorious indecision is life itself -- the sure knowledge that if we can live with ambiguity, we'll live better, have a lot more fun, and ultimately will make that better mousetrap.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Kuhn T., The Structures of Scientific Revolutions. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970. The entire book treats the character of scientific change. He discusses the Bruner and Postman experiment with anomalous playing cards in Chapter VII.