La Sylphide

Today, a ballet gives us an odd window into history. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I went to see the French ballet La Sylphide the other night. It is a tragedy that calls forth few tears. A Scottish farmer falls in love with a magical sylph and leaves his bride-to-be for her. He also offends the witch who predicted his defection. She avenges herself by killing him and the sylph as well.

However, as writer Margaret Putnam tells about the background of La Sylphide, the ballet takes on complex coloration. It was first performed in 1832. By then, the social reform that'd brought in the Industrial Revolution was devolving into soot and squalor. Twenty years earlier, Luddites had struck the new textile factories. Then the Romantic poets had begun writing about Satanic mills and the loss of nature in a world being built upon coal and steel.

The ballet was part-and-parcel of the back-to-nature movement. The setting imagines a world in the Scottish highlands where fairy creatures live. However, the sylph itself is not exactly the stuff of fairy tales. It is instead a creature of alchemy. The alchemist Paracelsus imagined that a creature called an "elemental" lived in each of the old Aristotelian essences, earth, air, fire, and water. Nymphs were water creatures, gnomes were of the earth, and salamanders dwelt in fire.

But the highest creature was the sylph, the winged elemental who lived in the air. And we suddenly find ourselves in a spider's web of changing ideas. For one thing, 250 years of empirical science and rationalism had replaced Paracelsus' alchemy. By 1832, the Romantics were saying it was time to rediscover the mind's alchemy. So our tragic heroine is a winged sylph, a Paracelsan elemental doomed to die in the aggressive world of humans around her.

But the renaissance world that was taking shape around Paracelsus had revived the male-dominated culture of ancient Greece. As the nineteenth century reacted against this neo-Grecian rationalism, women began reclaiming their role. Ballet, for example, had been centered on male athleticism. The first La Sylphide choreographer, Filippo Taglioni, cast his remarkable daughter Maria as the sylph. Maria Taglioni was a superb dancer. In one stroke, she redefined ballet, and she ushered in the age of the prima ballerina.

So a fantasy about simple life in the Scottish highlands spins out against a rapidly mutating world. Never mind that the English had just finished shipping the population of northern Scotland off to Canada and replaced them with a lucrative sheep-raising industry. This is the imaginary Scotland of Walter Scott or Brigadoon.

At length, our star-crossed sylph is wrapped in the wicked witch's poisoned shawl. Her tiny wings fall to the floor like fish scales, and the old alchemy is pronounced dead. Yet the sylph died at the very moment when people like Faraday, Darwin, and Maxwell were about to rebuild European science. And they did so by calling up a renewed alchemy of human thinking.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Putnam, M., Lighter Than Air. Houston Ballet Stagebill, Winter, 1999, pp. 14-15, 24, 58.

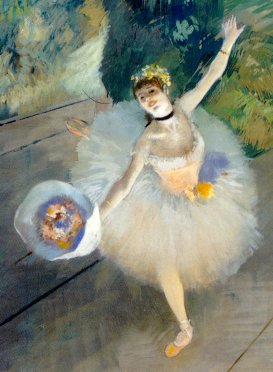

The nineteenth-century age of the ballerina

(Detail from Edgar Degas', Dancer Taking a Bow, 1877)