Max Jakob

Today, a great engineer escapes the Holocaust. The Universty of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

In 1937 Max Jakob and his family got on the steamer Berengaria in Cherbourg, France, to make a stormy six-day crossing to New York. He was leaving his German homeland for good. He limped slightly as he walked up the gangway -- the result of a wound on the Russian front in WW-I. He was now 58 years old and a prominent German expert in the field of heat transfer.

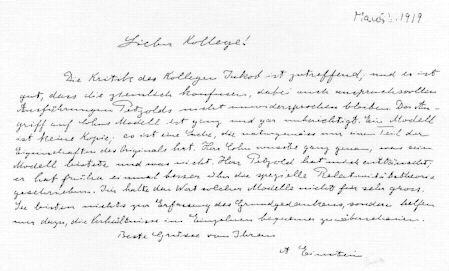

For 31 years -- ever since he'd finished his doctorate in Munich in 1906 -- Jakob had worked on the central questions of the thermal sciences, and he'd been involved with the greatest scientific minds of his era. His daughter Elizabeth shows us correspondence. Here's a postcard from Einstein, who was born and died within months of Jakob. Einstein thanks him for setting a critic straight on relativity. There's a letter from Max Planck, thanking Jakob for correcting an error in his paper.

But now he's boarding a boat to America. Four years before, German troops went through Berlin painting the word JEW in large white letters on store windows, and Jakob wrote in his diary,

I never valued my Jewishness as much; but today I'm happy not to be on the side of those who tolerate this.

First, he'd sent his daughter off to college in Paris. Now he and his wife were also leaving what had seemed the intellectual and cultural center of the universe. They were moving to the land of gangsters and Al Capone -- to Chicago, whose climate he'd been told was murderous. They were each allowed to take $4.00 out of Germany.

Jakob's move proved to be terribly important for us. America was far behind Germany in its understanding of heat flow, and we were working hard to make up ground. Jakob gave us the first direct conduit to that knowledge.

And America was a pleasant surprise for Jakob. The first photographs show him smiling and inhaling the fresh air of a new land. Once here, he discovered -- and took pleasure in -- civilization of a different form, but civilization nevertheless. He found youthful excitement in the intellectual climate, and he became a part of it. He gave us every bit as good as he got. Many of today's elder statesmen in the field were his students, and everyone in the field knows his work.

His daughter finds a diary entry the week before his death in 1954. He'd just been to hear the great Black contralto, Marian Anderson. He was strongly moved by her singing of, and I quote,

the magnificent Negro spirituals, especially 'Nobody Knows the Trouble I've Seen' and 'He's got the Whole World in His Hands.'

By then America had become the world leader in heat transfer. And Jakob, who'd helped us so much to get there, was one of the great American engineers and educators.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

This episode has been rewritten as Episode 1546.

(Letter provided by Max Jakob's daughter Elizabeth)

Letter from Einstein to Max Jakob thanking him for defending relativity theory