Indian Telegraph

Today, telegraphy comes to India. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

In 1856 the British completed a 4000-mile Indian telegraph system. It connected Calcutta, Agra, Bombay, Peshawar, and Madras. The telegraph was the brainchild of a visionary inventor named William O'Shaughnessy, and it secured England's grip on India.

O'Shaughnessy had gone to India in 1833 as a 24-year-old assistant surgeon with the East India Company. There he began experimenting with electricity. He invented an electric motor and a silver chloride battery. Then, in 1839, he set up a 13½-mile-long demonstration telegraph system near Calcutta.

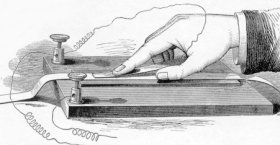

That was only two years after Samuel F.B. Morse built his famous demonstration system in the United States. But O'Shaughnessy was unaware of Morse's work. His telegraph used a different code and, at first, he transmitted the message by imposing a series of tiny electric shocks on the operator's finger. He also came up with another unique invention. He used a 2½-mile stretch of the Hooghly River, in place of wire, to complete the circuit.

O'Shaughnessy published a pamphlet about the system, but he failed to ignite any interest in telegraphy. Finally, in 1847, Lord Dalhousie took over as Governor General of India. Dalhousie showed real vision in developing public works. He initiated roads, canals, steamship service to England, the Indian railway, and a postal system.

Of course it was Dalhousie who saw the potential of O'Shaunessy's telegraph. He authorized O'Shaughnessy to build a 27-mile line near Calcutta. That was running so successfully by 1851 that Dalhousie authorized him to build a full trans-India telegraph. O'Shaughnessy finished it three years later.

It was an amazing triumph over technical and bureaucratic problems. By then O'Shaughnessy knew about the new English and American telegraph systems, but that was more hindrance than help. It simply meant he had to invent his own equipment to avoid patent disputes. He also had to work with local materials, environments, and methods of construction. He had to invent his own signal transmitter and create his own means for stringing lines.

While the system was still under construction, it helped the British in the Crimean War. Three years later, the full system so networked British rule that it was decisive in putting down the Sepoy Uprising. One captured rebel, being led to the gallows, pointed to a telegraph line and bravely cried, "There is the accursed string that strangles us."

So question nineteenth-century British colonialism if you will. There is much to question. But you can only admire O'Shaughnessy. He showed what one person can do by trusting the creative ability that's there to claim. He stands as a reminder that one person can make a difference.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Gorman, M., Sir William O'Shaughnessy, Lord Dalhousie, and the Establishment of the Telegraph System in India, Technology and Culture, Vol. 12, No. 4, October 1971, pp. 581-601.

See also the entry under O'Shaughnessy in the Dictionary of National Biography and the entries under India and Dalhousie, James Andrew Broun Ramsay, in editions of the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

This is a considerably revised version of Episode 54.