George Squire

Today, a story about altruism and Muzak. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

When I was assigned to work on communications equipment at Fort Monmouth's Squire Lab in 1954, I vaguely wondered who Squire was. Now, 44 years later, I open Invention and Technology magazine and find a 1925 photo of General George Squire, with a bowler hat, celluloid collar, and pince-nez, glowering at the photographer. Squire, it seems, was frowning over a long legal battle with AT&T.

Squire was born in 1865. He went to West Point, then devoted his life to science, engineering and the Signal Corps. He worked on electric tracking of projectiles and was an early proponent of flight. He was almost alone in supporting Goddard's rocket experiments. Squire was far more interested in science than war. A 1905 War Department memo said he seemed to have "no relish for line duties." Of his personal life we know next to nothing. Indeed, he worked with such intensity we wonder if he had a personal life.

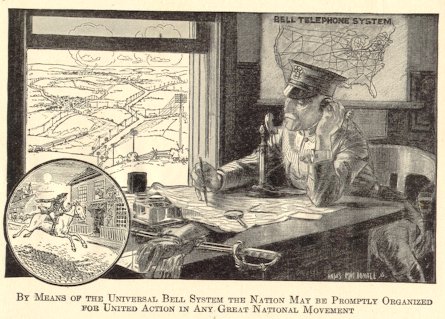

For forty years he pioneered communication systems, especially wire-wireless systems. That meant superimposing high-frequency radio signals on low-frequency telegraph lines. That way, radio signals could be sent out without being broadcast to local receivers. The wires, unlike telephone wires, didn't have to be insulated. And the high frequency didn't interfere with telegraph signals. It was an important and revolutionary idea that's used in many ways today.

Squire did a surprising thing with his patent. The 1883 patent law let him assign it to the government so that any American citizen who wanted to could use it. When he did that, he misjudged the forces of avarice. His patent was immediately put to use by AT&T.

Then, to gain exclusive control, AT&T claimed Squire had infringed on their earlier patents. Squire had tried to share his discovery, and now he found it monopolized. He took AT&T to court (hence that grim 1925 photo). It was a legal battle he couldn't win, but as it ground on he found a new use for the technology:

In 1915 Edison had tried putting a phonograph in a cigar factory to improve production (I wonder if he played Carmen!) It seemed to work, and in 1922 Squire found that he could send radio music over power lines. He formed a company called Wired Radio and began selling canned music to businesses -- especially hotels and restaurants. He arbitrarily combined the words music and Kodak to get the catchy word Muzak. But AT&T also liked that idea, and they eventually gained control of it as well.

In the end, Squire retired to a large Michigan farm, which he freely opened up to the public for hunting, golf, and fishing. He took in 60,000 visitors a year. His generosity, which was beaten in the courts, finally found expression in this odd open-handed gesture.

Of course Muzak on elevators is hard to love. We listen to Public Radio because we want better. Still, Muzak is emblematic of Squire's recurring impulse to give something away to all of us.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Lindsay, D., The Muzak Man. American Heritage of Invention & Technology, Vol. 14, No. 2, Fall 1998, pp. 52-57.

Thirteen years after Squire first used telegraph lines for radio, the 1923

Wonder Book of Knowledge still talks about using secret codes to protect

the secrecy of military information being broadcast over radio telephones.