The Mississippi

Today, a River in 1883. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Mark Twain wrote his great epics about the Mississippi between 1876 and 1884: Tom Sawyer, much of Life on the Mississippi, and finally Huckleberry Finn. Mark Twain wrote that river into our imaginations. That's why I was so arrested by something I recently found in a bookstore. It was an old travelogue, published just before Huckleberry Finn, with the title America Illustrated.

The article traces the Mississippi, not from its official headwaters in Lake Itasca, but from a pool further north which feeds Itasca. From there it flows down to St. Anthony Falls just above St. Paul. Riverboat traffic divided into two regions: one above the falls, the other below that natural obstruction.

Mark Twain's Mississippi lay below the waterfall. The rich texture of his River forms itself around Missouri. And here we find a time-warp. For Twain mixes the River of the 1840s with that of the 1880s. Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer were children of the 1840s, and their stories are filled with anachronisms simply because the world was changing so rapidly.

By 1874 the great third-of-a-mile-long St. Louis Bridge had linked Missouri to Illinois. Twain's bucolic world was giving way to modern Midwestern America. In fact, Mark Twain's flat-bottomed river boats weren't yet fully evolved when Huck Finn travelled the River. The Mississippi of the 1840s was more primitive than he described it. Another great novelist, Charles Dickens , visited the River in 1842, and his account is shocking. When Dickens saw the town of Cairo, where the Ohio enters the Mississippi, he wrote:

We arrived at a spot more desolate than any we had yet beheld ... On ground so flat and low ... it is inundated to the house-tops ... a breeding place of fever, ague, and death. A dismal swamp, on which half-built houses rot away ... teeming with rank unwholesome vegetation in whose baleful shade the wretched wanderers ... tempted hither, droop, and die, and lay their bones; the hateful Mississippi circling and eddying before it, and turning off upon its southern course, a slimy monster hideous to behold.

My great-grandfather came to the River soon after Huck Finn's time — in the 1840s — and he recorded a similar world. Later he bought a house in Illinois near the River. That same house became the set for the movie version of Tom Sawyer. But in the movie the house appeared as great-grandpa had arranged it by the 1870s, while Mark Twain was writing the book. The house in the movie matched the house in the story.

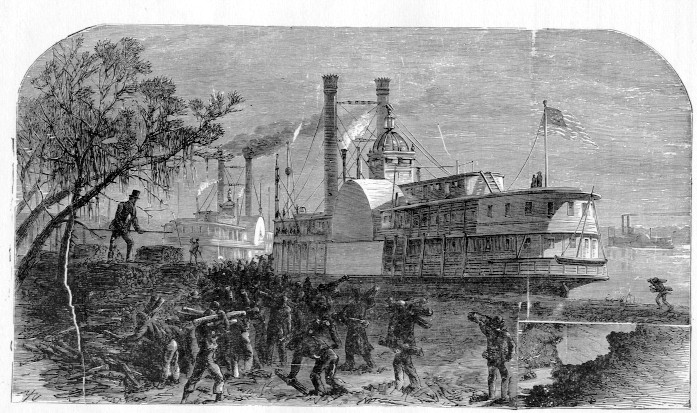

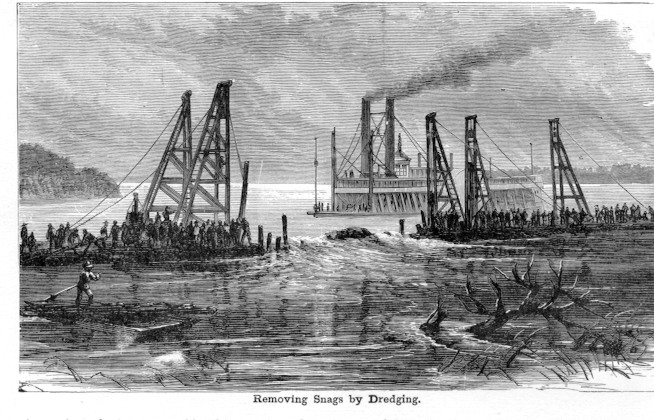

My old travel book is richly illustrated with Mark Twain's river boats — flame leaping from their stacks against the night sky, their covered side-wheels driving them upriver from New Orleans, dodging snags and sandbars. But that was 1883.

The rich images leave me puzzled. For Mark Twain's River was a time composite. It is the River we all know, and yet it is the River that never really was.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

America Illustrated. (J. David Williams, ed.) Boston: deWolfe, Fiske & Company, Pubs., 1883.

For the complete text of Dickens's American see the website: https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/675

I am grateful to Dorothy Baker, UH English Department, for her counsel on this episode.

For full-size images, click on the thumbnails above.

Left, "Wooding up" a steamboat. Right, Removing Snags by Dredging.

From America Illustrated, 1883