Cinqué

Today, art and slavery. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The movie Amistad tells the true story of a group of Mende people taken into slavery. In 1839 they overcame their captors on the Spanish ship Amistad (which, by the way, means friendship). By day the Africans forced the surviving Spaniards to head east toward Africa. By night the Spaniards turned the boat back toward Cuba. Their zig-zag course finally deposited them in Long Island Sound.

The Africans were arrested and put on trial while pro- and anti-slavery forces took sides. Some preposterous legal maneuvering followed. The United States wanted to return the Africans to Spain to honor a treaty obligation. So they charged the Africans with violating American anti-slave-trade law by bringing a slave ship into American waters. It finally took the Supreme Court to set them free and put them on a ship back to Sierra Leone.

Now art historian Richard Powell goes back to those times to offer us a window into American attitudes surrounding the trial. His article is titled Cinqué, which is what the Spanish called the 25-year-old revolt leader, Sengbe Pieh.

America had by then created its own school of portrait painting in an attempt to rival Europe. While European portraiture presented the aristocracy, ours became a popular reflection of the egalitarian spirit of the Revolution. By 1839 portraits decorated every drawing room. And what could complement those ideals as perfectly as the tall, handsome young African, Cinqué!

Robert Purvis, a wealthy free black Philadelphian, went to a New England abolitionist artist named Nathaniel Jocelyn and hired him to paint Cinqué. Jocelyn was a fine painter, and Purvis had not miscalculated. While the case was grinding through the courts, Jocelyn finished a picture that fully expressed his own passion for the abolitionist cause. He shows Cinqué in a Roman-style toga, holding a cane rod which might as well be a royal sceptre. Cinqué's eyes look off past the viewer's left shoulder.

By 1840 we had color lithography to mass-produce images. The abolitionists printed hundreds of copies of Cinqué's portrait; it became a rallying point for their cause. That was a two-edged sword. Jocelyn had shown Cinqué as a noble Roman. But he'd also shown a defiant Roman whose cane staff might well be a weapon in his fight for freedom. This Cinqué was a force to be reckoned with. His gaze, drifting past us, suggests that we white viewers are obstacles to be bypassed. He did little to ease white fears.

And so the portrait kept stirring passions long after the Amistad case was settled. It stands as one of the great pieces of political art. Perhaps the surest sign of its political power is to be found in the movie version of the Amistad story. For there stands Cinqué on the deck, clad in that same white toga -- wind-blown, noble, and in command. The movie shows us Jocelyn's Cinqué. And, we realize, that may well may be the truest Cinqué after all.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Powell, R. J., Cinqué: Antislavery Portraiture and Patronage in Jacksonian America. American Art, Fall, 1997, pp. 48-73

These two sites give the texts of John Quincy Adams's defense of the Africans before the Supreme Court and the Supreme Court's decision:http://www.historycentral.com/amistad/amistad.html

http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?court=US&vol=40&invol=518

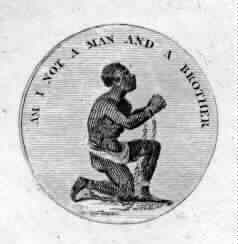

Below is a block-print copy of an anti-slavery medallion cast by Josiah Wedgwood in 1787 in black basalt on white jasper. It was one of the first widely distributed images that spoke to the public about the evils of slavery.

From Erasmus Darwin's Botanic Garden, 1799.

Image courtesy of Special Collections, UH Library