Stability of Pagodas

Today, pagodas and earthquakes. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Japan is earthquake country. For centuries no one made multistory buildings in Japan. Not 'til 1968 did Japanese engineers have enough confidence to erect a 36-story, earthquake-resistant building in Tokyo.

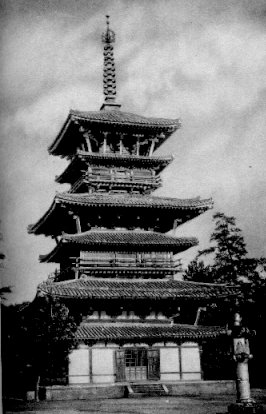

Yet one kind of high-rise building had been common in Japan for over 1400 years. Scattered over Japan are 500 pagodas that rise vertically to heights of as much as 180 feet. Those pagodas have been rattled by countless earthquakes, and they still stand, serene and unruffled. You know the image: towers with multiple roofs stacked above one another. They're like Christmas trees, rising to a decorative spire. You expect to find a star on top.

When you see how pagodas are built, you think you've found a recipe for collapse. Each roof carries heavy tiles. A central pole, the trunk of a huge cedar tree, is the core on which the structure hangs. But that pole isn't anchored in the earth. In fact, it sometimes doesn't even reach all the way to the ground. The weight of a pagoda is carried entirely on supporting pillars which form a small open porch on which the pagoda sits. It seems to make no sense, yet pagodas stand, centuries in and centuries out.

Now The Economist magazine goes to Shuzo Ishida at the Kyoto Institute of Technology. Ishida is called "Professor Pagoda," for he knows more about those mysterious structures than anyone living. He explains their peculiar damping properties: When an earthquake shakes a pagoda, those massive roofs try to slide sideways, but the pole won't let any roof move very far. It flexes sideways, bending to drive neighboring roofs the opposite way. During an earthquake, the pagoda does a kind of shimmy, or snake-dance, with each roof damping out the motion of its neighbors.

The next time you drive past a large power transmission line tower, notice the way a slack length of cable often links the power line on one side to that on the other. The purpose of that cable is to pass wind-driven vibrations, out of phase, from one side to the other. The vibrations spend themselves opposing each other.

So it is with the pagoda. Buddhist philosophy tells us to let our enemies collapse under their own weight. These Buddhist pagodas let the devastation of an earthquake fight itself along the length of that cedar pole -- called a shinbashira. It's good engineering, worked out over centuries by trial and error and finally verified by modern dynamic analysis. The Economist article ends with these marvelous words:

The idea that the shinbashira could be as much a religious object as a dynamic balancing device for dampening the destructive forces of earthquakes and typhoons is attractively reassuring. God is in the details, after all.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

An Engineering Mystery: Why Pagodas Don't Fall Down. The Economist, Dec. 20th, 1977, pp. 121-122.

I am grateful to Winston P. Crowder of Houston, Texas, for providing the article and suggesting that I do an episode based upon it.

A Pagoda at Nara, Japan

In the Background, a Pagoda in Osaka

Two Japanese Pagodas from Sturgis's A history of Architecture, Vol. II, 1909

Images courtesy of the UH Art and Architecture Library

Another Pagoda at Nara

Photo by John Lienhard