Railroads in Winter

Today, rails and snow. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I boarded a train in Seattle, in early October, 1953. The army was shipping me to basic training in Virginia. For two days we crossed America's vast high plains under gray skies. Winter wasn't there yet but it would be soon. Winter would pile great drifts of snow around tracks running through the middle of nowhere.

Winter plagued the early American railways. Engineers felt their way across our great landmass in the years before 1869, when Union Pacific finally linked East and West. Snow blocked travel in winter, and the spring melt washed track away.

By a sometimes grim process of trial and error the railways learned to elevate tracks to protect them from runoff and to anchor trestles so snow slides wouldn't sweep them away. They also had to invent new technologies of snow removal. Anyone raised in the American North grows up knowing how vicious snow can be.

America's first commercial railroad was built in 1827. We were seriously in the railroad business by the mid-1830s. At first trains carried crews of men armed with shovels during the winter. By 1840 railroad engines were equipped with V-shaped plows.

But tackling the implacable high plains and rocky mountains would take more than simple plows. A blizzard could fill a road cut higher than the train itself. Annual temperature variations of 140 degrees warped track and derailed trains. Disasters quickly taught the railroads new technologies of track laying and routing. When monster plows, driven by many engines, still weren't up to the task of snow removal, they created snow sheds -- wooden tunnels built along the sides of mountains to keep the snow off the tracks.

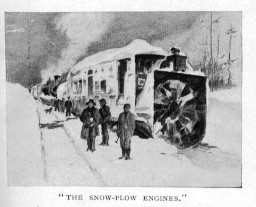

In 1884 a Canadian mill-owner with the odd name of Orange Jull created the rotary snowplow. It looks like a great electric fan mounted on the engine, eating its way through snow, chewing it into powder and blowing it out the side. Rotary fans are still the best way to clear snow, but they're not the whole answer -- not when a slide can deposit snow inlaid with trees and boulders.

By now snow clearance is a pretty mature technology. But it's also one without which America could not've been linked together. The 19th century is filled with stories about passengers stranded in the middle of Wyoming or the Dakotas, burning the engine's coal to keep from freezing. Stories abound of walking across frozen rivers to get from one rail head to the next. In 1876 Walt Whitman wrote a prophetic poem, To a Locomotive in Winter:

... pulse of the continent,

Law of thyself complete, thine own track firmly holding,

Thy trills of shrieks by rocks and hills return'd,

Launch'd o'er the prairies wide, across the lakes,

To the free skies unpent and glad and strong.

Whitman was oddly ahead of himself. It'd be another forty years before railroads had that kind of solidarity in winter. But they would. And he saw it coming.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Allitt, P., How the railroads Defeated Winter. Invention and Technology, Winter 1998, pp. 55-67.

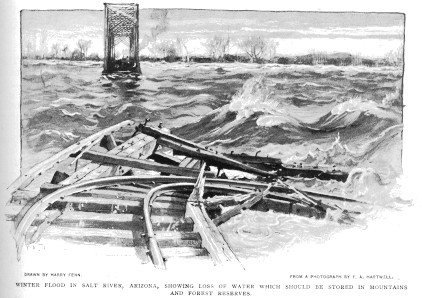

As late as 1895 the assault of the Spring floods was very

much on the mind of this artist for the Century Magazine.

A sketch of a rotary snowplow from the same

June, 1895, issue of the Century Magazine.