Darwin Boards the Beagle

Today, a young man boards a ship and redirects history. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The year is 1831. A 22-year-old student presents himself for the post of ship's naturalist on a long voyage of exploration. He does so at the urging of a professor and over his father's objections. In a London office, he meets the captain, who is himself only 26. The two form a powerful affinity and the student is hired.

The student was Charles Darwin -- just graduated from Cambridge. Darwin had been an undistinguished student, but he'd shown a real flair for natural history. The captain was Robert Fitzroy, an intense religious fundamentalist and strict charismatic leader. The ship was a brig, only 90 feet long, named the Beagle. Fitzroy had been given command of the Beagle when he was only 23.

The purpose of the voyage was twofold: to chart the South American coast, and to check longitudes around the world with a set of chronometers. Adding young Darwin was an afterthought -- a way to squeeze a little more scientific data out of the long trip.

As Darwin prepared to sail, he sensed what he had no way of knowing -- that he was sailing into history. To his sister he wrote, "There is indeed a tide in the affairs of men and I have experienced it." To Fitzroy he wrote that the sailing date would be "as a birthday for the rest of my life."

When the Beagle sailed, 3½ months later, Darwin stayed seasick all the way to the Cape Verde Islands. But when he saw his first volcanic island, just as Lyell had written about in his famous geology text, Darwin he realized that he too might write a book some day. He eventually wrote many books, including one about volcanic islands off South America. But it's The Origin of Species that we remember.

The last data Darwin needed for a theory of evolution lay in the Galápagos Islands off the west coast of South America. When Darwin reached the Galápagos after four years exploring the South America coast, he found its plant and animal life had grown apart from that in South America. Its evolution had been isolated.

The Galápagos put in perspective all that Darwin had seen in South America. It would be 27 years before Darwin published his theory of evolution. But after the Galápagos, that theory was inevitable. And when it came out, Charles Lyell, whose book had so reached Darwin, was an important early convert to it.

Fitzroy was another story. That charming, intense fundamentalist had befriended Darwin. His long conversations had sharpened Darwin's arguments. Fitzroy went on to become an admiral.

But Darwin's theory was too much for him. In 1860, he showed up at a church sponsored debate on evolution at Oxford University to rage against his old friend. Five years later, in a fit of righteous frustration, Fitzroy cut his own throat. He'd been first to see the genius in the boy. But, in the end, Darwin asked us to accept more change in the very nature of things than many people could bear to accept.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Moorehead, A., Darwin and the Beagle. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1969.

See also articles in various editions of the Encyclopaedia Britannica on Darwin and Fitzroy.

For more on Darwin's voyage on the Beagle, see Episode 617.

The complete text of Darwin's book, The Voyage of the Beagle, is included in this Gutenberg Project website

For a full-size image click on the thumbnail

The Beagle off the southern coast of South America.

Image courtesy of Special Collections, UH Library

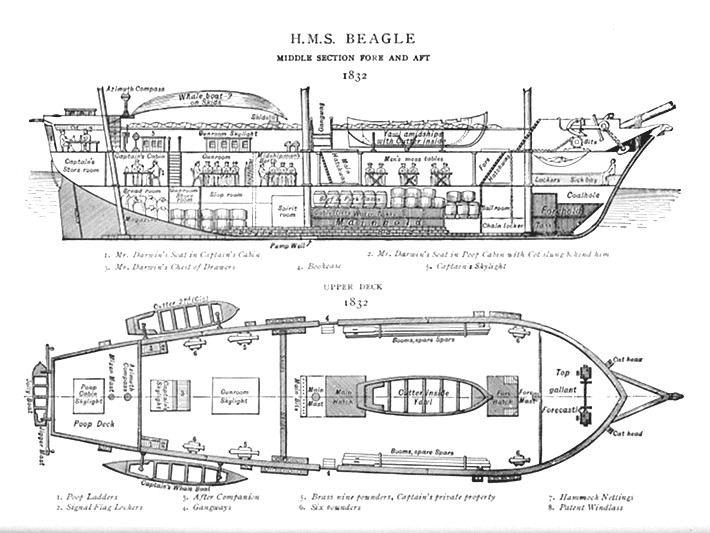

For a full-size image click on the thumbnail

Cutaway drawings of the Beagle

Image courtesy of Special Collections, UH Library

Both images from the Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited during the Voyage Round the World of H.M.S. 'Beagle', 1913.