Charles and Hester Stanhope

Today, a prime minister's niece doesn't get the message. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

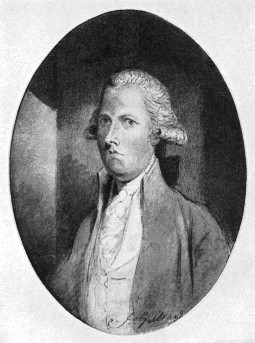

The amazing William Pitt was only 24 when he first became prime minister of England in 1783. Pitt was an incorruptible reformer. Yet he never traveled, had limited knowledge of human nature, and lived outside the intellectual mainstream. He was a lonely, tightly-wired spendthrift who died penniless at 47 after a nervous breakdown during his second term as prime minister.

Pitt's sister had married Charles Stanhope, borne three daughters, and died young. Charles's second wife took little interest in the daughters. Their schooling and upbringing were haphazard.

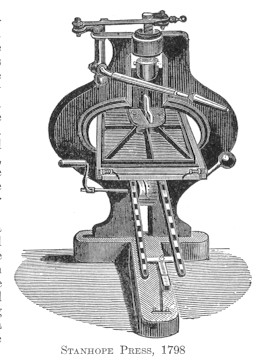

But Charles had his own erratic genius, which he divided between politics and invention. As a member of parliament under Pitt, he'd opposed England's war against the American Colonies and supported the French Revolution. As an inventor he created the powerful Stanhope optical lens. He also invented the first iron printing press -- the first step away from the old winepress screw that'd been used since Gutenberg to press inked type against paper.

The Stanhope Press led the way to high-speed presses which made books cheap and available in the 19th century. He'd sown practical as well as political seeds of a new equality. But his revolutionary message seemed not to register with his daughters.

Three years before his death, Pitt had asked Charles's eldest daughter, Hester Stanhope, to manage his household. Hester had all her family's brilliance, but she put it to shaping a place within the rarified atmosphere of the 18th-century rich. Pitt pampered Hester. The aristocracy loved her sharp undisciplined tongue. She was vain and self-dramatizing and had commanding personal magnetism.

When Pitt died, Hester lost access to his lavish spending. So in 1810, now 34, she gathered a small entourage and set off for the Middle East. Adventure followed adventure. In Greece, she met young Lord Byron (who found her annoying). Later, she was ship- wrecked off the island of Rhodes. Finally, the Pasha of Acre gave her the ruins of a convent on Mt. Lebanon. She began dressing like an Arab, and she made the old convent into a medieval fortress.

For 25 years she maintained 30 native servants and entertained European visitors who came to hear her rambling harangues. London followed her in the papers. She fed beggars, defended the Pasha against Druse uprisings, and became a frightening Holy Woman for the locals. When she'd spent all she had, she ran up huge debts. She smoked hash, grew sick, and turned old far beyond her years.

Why don't you cut your staff, a friend said. Think of my rank and appearances, she snarled. When she died in 1839 her servants stole all but the clothes and jewelry on her body. She'd barely outlived the old order of English aristocracy without understanding the political and inventive reforms her father and uncle had put in motion. In the exotic fortress of her powerful personality, Hester Stanhope had clung to the last outpost of imperial excess.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Haslip, J., Lady Hester Stanhope. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company Publishers, 1934.

See also the Encyclopaedia Britannica and Dictionary of National Biography entries on William Pitt and Charles and Hester Stanhope, as well as various texts on printing, optics and the history of technology.

From The Wonder Book of Knowledge, 1923

William Pitt

From the October, 1895, Century Magazine.