Sarah Bagley

Today, a woman claims a job market for other women. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

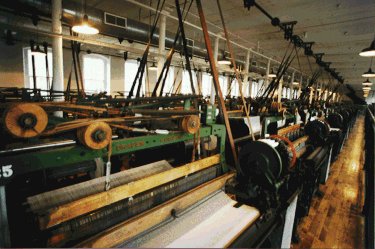

Madeleine Stern tells about Sarah Bagley, who went to Lowell, Massachusetts, in 1836, to work in the new spinning mills and in the Hamilton watch factory. Lowell was just hitting its full stride as a model industrial city. Those industries had organized boarding houses for young women like Sarah Bagley -- houses that managed the women's lives and looked after their morals and education on the side. Lowell's model system was both ahead of its time and very paternalistic.

After nine years of that, Bagley was turing into an early member of the American labor movement. She studied writing at a local Universalist church. She began submitting articles to The Lowell Offering, a magazine tightly controlled by the factories.

Then, on the 4th of July, 1845, she spoke at a workers' meeting in Woburn, Massachusetts. She objected to a plan for increasing the workday from ten to twelve hours, and she got in several licks against control over The Offering. She warned "the mushroom aristocracy of New England" that "our rights cannot be trampled upon with impunity." In 1846 she took over as editor of a new magazine, The Voice of Industry, and began pushing radical reform in earnest.

The labor movement was still embryonic. Factories weren't yet hiring Pinkerton guards to go about cracking skulls. What actually did happen was good news. The same year she began her new magazine, Morse's new telegraph system came through Lowell on the way from New York to Boston. Morse's representative was a man named Francis "Fog" Smith, a risk-taker in an unstable new technology.

Fog Smith recognized a kindred spirit in Bagley. He hired her out of the mills to run the Lowell telegraph office. Bagely spent a few weeks studying the electro-mechanical system and then went to work. Years before, she'd written an article for The Offering in which she told how the "complicated, curious [factory] machinery" opened up one's mind. She was more than just comfortable with new technology, she found it stimulating.

The local press treated Lowell's new telegraph line as a joke. One paper wrote, "The maximum of the magnetic attraction [of humbug] is always at the center [of humbug]." Another, skeptical about women in the telegraph office, asked, "Can a woman keep a secret?" And so for a salary of around $400 a year, the first woman telegrapher set about to make this new workplace a plausible one for women -- cleaning the batteries every night, acting as information headquarters for Lowell. A vocation, which might well have turned all-male, went to both men and women just because of Bagley.

After 1846, Sarah Bagley vanished from history's records. Did she marry and change her name? Did she die young? We don't know. For us, she lingers only as a brief, bright, and terribly influential stitch in our complex national tapestry.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

1.Stern, M. B., We the Women. New York: Schulte Publishing Company, 1963, Chapter 4.

For more on Lowell see Episode 159.

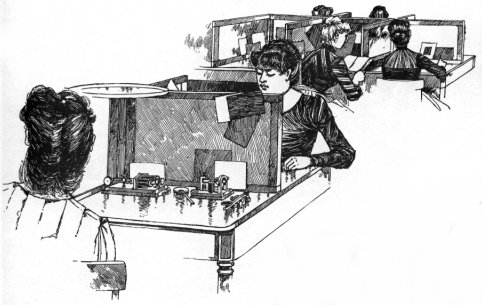

Women telegraph operators at work just a few years after Sarah Bagley

Lowell Mills Restored and Running Today

Photo by John Lienhard