Looking for Franklin

Today, we go looking for a lost explorer. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Oh, how England loved her explorers! Small wonder they undertook heroics that shock us in our comfortable lives today. When the American, Stanley, went looking for Livingstone in 1872, both countries followed the search the way we follow basketball. Those heroics expressed the ideals of empire, along with all that was bad about imperialism. Livingstone got into trouble with the missionary society for caring more about exploration than church work.

In another episode, we talk about the catalyst for much of that -- the search for Sir John Franklin. Franklin set out with two ships to look for a Northwest Passage in 1845. After one year, with no word, people didn't worry. After two years, they wondered why he hadn't been able to get a message back with the help of the Eskimos. After three years people knew something was wrong. After four years, his wife joined with the government to offer a prize of £20,000 for anyone who found him.

So search parties went out. During 1850, at least ten English and American expeditions were searching for Franklin. They suffered, they died, they established our knowledge of the Arctic. But they didn't find Franklin. They did locate a route to the Pacific where only bits and pieces of the ice broke up during the summer. No ship got through the passage in one season until 1944.

In 1857, Franklin's wife outfitted another search. That one found Inuit natives who told of a ship that'd broken up in the ice -- whose crew had tried to walk out. Their search went on for three years and it turned up a few scattered relics of Franklin's people.

By the late 1860s, an American explorer learned that five of Franklin's starving men had actually survived, found their way to Alaska, and been rescued by natives there. The last of them died in 1864 without ever finding a way home.

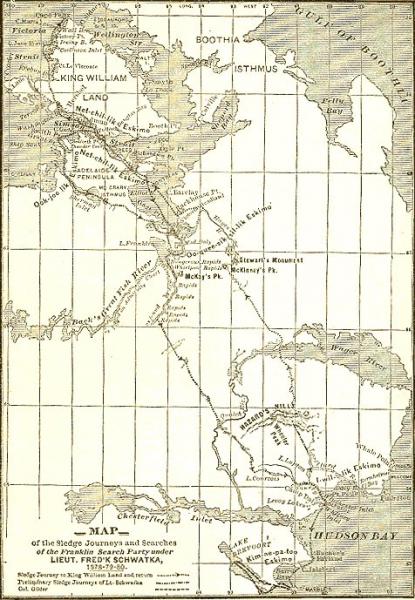

Finally, in 1878, an American, Frederick Schwatka, and two companions decided not to mess around with ships. They got off a whaler on the north shore of Hudson's Bay and hired 13 Inuit guides. They set off to the north in good hands.

Gradually Schwatka and his companions learned Franklin's terrible story. Scattered groups, starving, eating their dead. A cairn here, a boat with skeletons there. A small book tells Schwatka's story, and the Inuit Indians form a kind of Greek chorus for all that heroic folly. Schwatka writes,

The Eskimos, as we know, are woefully deficient in almost everything that civilization has taught us to value and appreciate; but the deficiency has not affected their cheerful and genial disposition.

Those were the last days of the old empires. Countless heroes, all wearing cultural blinders, finally found out what really lay north of Canada. Finally the rest of us had learned the lay of that forbidding land -- which had been home to the Inuits, all along.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

The Search for Franklin: A Narrative of the American Expedition under Lieutenant Schwatka. London: T. Nelson and Sons, Paternoster Row, 1888. (No authorship indicated, although Schwatka wrote parts of it.)

See also Episode 1240, your library's catalog, and Encyclopaedia Britannica entries -- especially those from the older editions. A great deal was written about these explorations during the 19th century.

Click on the image for an enlargement

From The Search for Franklin, 1888

Image courtesy of Special Collections, UH Library

Click on the image for an enlargement

Lt. Schwatka's trip (from The Search for Franklin, 1888)

Image courtesy of Special Collections, UH Library