Hindenburg in Flames

Today, we ask, "Why did the Hindenburg burn?" The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

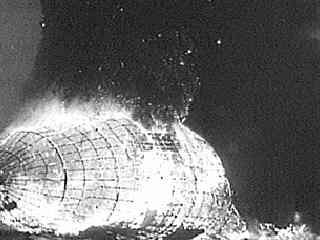

What child of the 1930s doesn't remember the Hindenburg! That great silver whale, the length of three football fields, its tail emblazoned with swastikas, black on red, that hydrogen conflagration waiting to happen. Since 1936, it'd carried passengers across the Atlantic. Then, 60 years ago this May 6, 1997, it caught fire and was consumed within 32 seconds. The radio announcer wept, "Oh, the humanity," as it went down. Yet, miraculously, two out of every three passengers survived.

It seemed so obvious in retrospect. Hydrogen is unstable in air's oxygen. All you need is a spark. Conspiracy theories followed the disaster, but they fared poorly against so much hydrogen.

There was a catch, but with all that hydrogen who would notice it? It is that materials don't burn in hydrogen. It's only hydrogen itself that burns, once it's mixed with oxygen. Then it creates a near-colorless blue flame -- nothing like the great fireball we remember each May 6th. Hydrogen-filled airships have been brought down by anti-aircraft guns without catching fire.

The first woman balloonist, Madam Blanchard, died in 1817 when she ignited the hydrogen in her balloon with a fireworks display. But the balloon didn't burn. Rather, the hydrogen burned off and the balloon dropped to a rooftop. She died only when the wind caught the unburned deflated gas bag and dragged her over the edge.

Now Malcolm Browne summarizes recent experiments being done to see why the Hindenburg burned the way it did. The result is something I should be poignantly aware of from my own model airplane building. I covered those models with damp tissue paper that dried taut as a drum. Then I drenched the paper in acetone-based airplane lacquer -- what everyone used to call dope. If you put a match to a model airplane, it went up just like the Hindenburg.

The Hindenburg's frame was likewise covered with canvas that'd been soaked in that same acetone lacquer. Worse than that, the lacquer had particles of aluminum mixed in with it to give the ship its silvery shine. At high temperatures, aluminum adds to the flammability. So the real fire hazard wasn't the hydrogen inside, it was the dirigible's skin.

Reports from Lakehurst, New Jersey, that stormy spring evening told of St. Elmo's fire dancing on the Hindenburg's upper surface. Whatever started the fire, the stuff that burned with such explosive speed was that terribly incendiary fabric. When that happened both the fabric, and the hydrogen being released, competed for the surrounding air's oxygen.

So we left off making great airships and we quit filling even our little blimps with inexpensive hydrogen. A whole era ended in a flash. It ended so quickly, that we're only now finding out what really happened -- on that terrible day so long ago.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Browne, M. W., Hydrogen May Not Have Caused Hindenburg's Fiery End. The New York Times, SCIENCE, May 6, 1997, pg. B-14.

Long after these arguments were raised in 1997, a group of engineers questioned them. See, e.g.: http://spot.colorado.edu/~dziadeck/zf/LZ129fire.htm

In particular, they argue that the ignition of the fire (which I have set aside in my own comments above) almost certainly originated in the hydrogen. They have also done lab tests that suggest a far lower burn rate in the fabric than was observed during the Hindenburg disaster. Since combustion of the fabric and dope has to occur in oxygen, not in hydrogen, this might suggest that the burn rate (oxidation) was accelerated in the Hindenberg by high temperatures generated as the surrounding oxygen and hydrogen reacted.