Baden Baden-Powell

Today, the empire finally takes to the air. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

A photo of Major Baden Baden-Powell, taken in his later life, looks like a character straight out of Kipling. Born in 1860, Baden-Powell lived most of his life in that British empire upon which the sun never set. Sun-burnt, mustached, hard-eyed, with a chest full of medals, he was a creature of another age.

A photo of Major Baden Baden-Powell, taken in his later life, looks like a character straight out of Kipling. Born in 1860, Baden-Powell lived most of his life in that British empire upon which the sun never set. Sun-burnt, mustached, hard-eyed, with a chest full of medals, he was a creature of another age.

Yet Baden-Powell wasn't quite what he appeared to be. He did join the Scots Guards at the age of 21. He saw action in the service of his Queen -- the Nile campaign, the Boer War, even WW-I. Throughout all that, his passion was not war, but flight.

You might recognize his name because his older brother, the Baron Robert Baden-Powell, is famous for founding the Boy Scouts. But young Baden Baden-Powell wanted to fly.

In 1880 he joined the Royal Aeronautical Society and soon decided they were too much talk, not enough action. So he bought his own balloon and learned to fly it. Within a year of joining the army, he was lecturing on military uses of lighter-than-air flight.

By that time, the American Army had made good use of observation balloons in the Civil War, and the French had used balloons to get mail out of Paris during the German siege of 1870.

In 1894, Baden-Powell made the first British military balloon flight. But he was a gadfly, a pot-stirrer, and a gatherer of information about flight. And his interests soon turned to man-carrying reconnaissance kites. (The Chinese had flown humans in kites 1300 years before him, but no one had done it in the West.) Baden-Powell developed a system of four kites along a rope, and it carried him as far as 300 feet up in a basket chair.

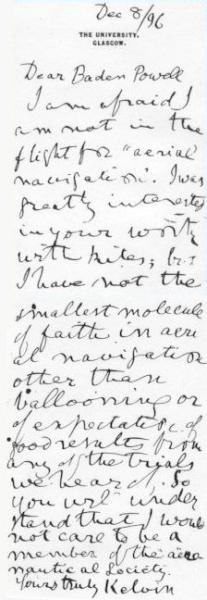

The Aeronautical Society had dwindled to three members when Baden-Powell set out to rebuild it. When he wrote to the great scientist, Lord Kelvin, Kelvin replied that he had "not a molecule of faith" in flight. No matter. Baden-Powell also wrote an article that spoke with a prescience worthy of Nostradamus.

What will the good citizens of London say when they see a hostile dynamite-carrying aerostat hovering over St. Paul's?

Forty-two years later we saw the dome of St. Paul's Cathedral by night, standing dimly against the smoke and flame of German bombs.

After his kites, Baden-Powell built gliders, then a powered airplane. He touched all aspects of flight. He really did rebuild the Aeronautical Society -- and he drove England to build the base of knowledge it needed to catch up with America and France.

And I'm back to that photo. A shy man; a stern man; a man with eyes that gaze outward and bore into you, but which look inward; a firmly controlled face; an uncomfortable mouth -- medals polished, buttons aligned. This is no warrior after all. Neither is it really an inventor. This is a visionary who has seen, with eerie clarity, a new world that he is bound to share with us.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Pritchard, J. L., Major B. F. S. Baden-Powell, Honorary Fellow, (1860-1937), An Appreciation. Journal of the Royal Aeronautical Society, Vol. 60, January 1956, pp. 9-24.

I am grateful to Alan Powell (no relation the Baden-Powells), UH Mechanical Engineering Department, for first bringing Baden Baden-Powell to my attention, and for lending me the Pritchard article. Image (which also appears in the Pritchard article) is courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

Letter from Lord Kelvin to Baden-Powell

indicating his disdain for aircraft