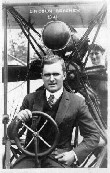

The First Daredevil

Today, the death of Lincoln Beachey. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Richard Reinhardt describes a scene on the shores of San Francisco Bay in 1915. Fifty thousand people watch a diver from the Battleship Oregon going down into the water. Then they wait -- and wait. An hour later, the ship's winch begins to turn. Out of the water comes a primitive airplane with its wings torn away. Still seated at the controls is the drowned body of Lincoln Beachey, 28 -- the first great daredevil of heavier-than-air flight.

Beachey was San Francisco's native son. He was arrogant, uncouth, and made of pure brass. Eleven years before, and only one year after the Wright Brothers flew, he'd made his first flight. He'd been one of several teenagers who rode across the Mississippi River on primitive balloons at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. Flight was on everyone's mind in St. Louis that year and Beachey was drawn to it like a moth toward flame.

At first Beachey flew the small dirigibles that were becoming regular state fair entertainment in the Midwest. Then, in 1910, he joined Glen Curtiss's flying school. He was a disaster -- crashing, breaking up equipment. But Curtiss recognized the fine madness of a daredevil and hired him to fly in his exhibition team.

There Beachey perfected every kind of stunt: flying down into the mists of Niagara Falls, flying to an altitude record of over two miles, nose-diving from 3000 feet with his engine off while onlookers screamed, fainted, and vomited. He did one of the first loops in the air and he did it hair-raisingly close to the ground. Prize money amply repaid his costs to the Curtiss flying school.

Lincoln Beachey and racecar driver Barney Oldfield had the same agent. Like Oldfield, Beachey was a PR person's dream. He told reporters he was consumed with remorse over deaths among pilots trying to outfly him. "Only one thing [drew audiences] to my exhibitions," he wrote. "It was the desire to see ... my death."

In that age of flying box-kites, nine out of ten exhibition fliers died. It was only a matter of time, and Beachey flew constantly. In 1913, his notices said, he'd entertained 17 million people in 126 cities. Each routine was closer to the edge than the last. He finally laid off for a year. Then he came back to San Francisco with a new plane for the Panama-Pacific Exhibition.

There he did a series of loops for the crowd, then climbed and dove far faster than he'd ever dived before. When he tried to pull out the wings tore off with a sickening crunch. The mayor was a pallbearer and school children made up a song for the occasion:

Lincoln Beachey,

Bust 'em green,

Tryin' to go to Heaven,

In a green machine.

So he made his last headline and then we forgot him. But he'd done the first thing that had to be done if we were to take to the air. He made such theater of flight that we all had to join in.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Reinhardt, R., Day of the Daredevil. American Heritage of Invention & Technology, Fall 1995, pp. 10-21.

For more on Lincoln Beachey, see the following website: http://www.amacord.com/fillmore/museum/beachey.html