Novgorod

Today, an old city coughs up a surprising secret. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Sergei Eisenstein's famous movie tells how Alexander Nevsky defeated the Swedes and Teutonic Knights in the year 1240 and saved Russia's leading city, Novgorod. It was a propaganda film warning the Nazis to stay out of Russia -- brilliant spectacle, driven by Prokofiev's haunting music, and peopled with cardboard warriors.

What the movie made less clear than the defeat of the Germanic forces was that Alexander's victory led to his son becoming the Prince of Moscow, and Moscow's eventual ascendancy in Russia.

Our knowledge of those medieval Russian times has depended on the chronicles of the courts. You see, early Russia was built of wood, not stone. And those buildings all normally perished by fire. Fire consumed the commonplace writings and artifacts, along with the buildings themselves. Russia has been shortchanged in the knowledge of her own history without such evidence.

But after WW-II, archaeologists realized that Novgorod sits on wet loam. Since the soil is wet, it doesn't absorb rainwater, or the oxygen that water brings with it. Once something gets into that soil, it's protected from decay. The upper parts of buildings may burn, but anything below ground level is preserved.

So archeologists have dug down into the dense wet soil below this 1200-year-old city. They find the artifacts of life before Alexander Nevsky. Most interesting are the writings. Householders didn't write on parchment (it was too expensive) or papyrus (they were too far from any sources) or paper (which had yet to come out of China.) They wrote on birch-bark. Some 700 well-preserved documents have turned up.

And what did people write about? Letters, poetry, formulas for potions, prayers, school work. The commonplace stuff you might find on your own shelves. The problem is, we'd thought that only priests wrote 800 years ago. Now we find not only that the burghers of Novgorod wrote, but that women wrote as well. We find marriage proposals. One letter from a woman to her lover says,

I have sent three messages to you. What grudge do you harbor against me that you have not visited me this week?

The words slash across the bark, written rapidly with mistakes, a few of which have been crossed over and corrected -- the rest left, as though to emphasize the force of her anger.

It's all so tawdry and ordinary that it's stunning. These aren't the laundered works of professional scribes. This is written language serving a people long before we thought it did. It seems more like the 19th century than the 12th. And we find all those literate women! The myth of women's ineptitude grew up in the renaissance, centuries later. It has taken archaeology to reveal, at last, an epoch that was far less primitive, and much better balanced, than anyone had realized.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Yanin, V. L., Letters from the Past: Insights into Russian Medieval Life in Novgorod. Science Spectra, Issue 1, 1995, pp. 42-46.

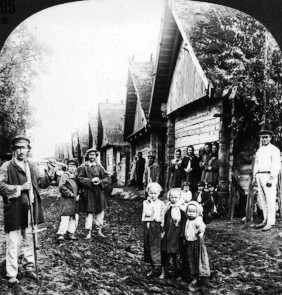

An early 20th century Russian village

Still medieval in character

Stereopticon image courtesy of Margaret Culbertson