Mirror

Today, we look in the mirror and find something strange. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

"Why don't you do a program on mirror images?"

says my wife. Now I'm in trouble! On the one hand, she's clearly on to something. On my other (mirror image) hand, I realize mirrors are such a familiar paradox we hardly have a vocabulary to talk about them.

Her remark was triggered by a program I did on chiral chemistry. A chiral material is one whose molecules are identical in every feature but one, and that one has to do with mirrors.

Suppose your mirror self were to step out of the mirror. His hair would be parted on the wrong side. His watch would be on the wrong wrist. There's no way you could turn him around to make him into you. He would not be you. That creature would be wrong in the same way as a left-handed handshake from a friend is wrong.

The word chiral comes from the Greek for hand, because our hands are mirror images. One chiral molecule is the reversed mirror image of the other. That means there's no way to rotate one molecule to make it into the other. That tiny difference is enough to make otherwise identical materials behave differently.

When I was young I saw the 1945 Michael Redgrave movie, The Dead of Night -- a set of six horror stories. The Dead of Night created conventions of movie terror we've used ever since. Everything in it has been copied 'til it's hackneyed. That was the first time I saw the trick of a mirror reflecting a scene unlike the one in front of it. Mirrors made me uncomfortable for years after that.

Engineers make great use of mirror images. Suppose a pipe carries hot water inside a concrete block, parallel with an insulated surface of the block. How to calculate heat flow in the concrete? The easiest way is to replace the insulation with a mirror image of the concrete and the pipe. It's far simpler to calculate the effect of the mirror image. And the answer's just the same as it is for the single real pipe.

The subtlety of mirror images shows itself in how long it took chemists to learn why seemingly identical molecules don't behave the same. Pasteur first found such molecules in 1847. But it was this century before people figured out the part of about chirality -- that the two molecules reflected each another.

Mirror imaging has become a regular tool in our bag of scientific and engineering tricks. Opposed images cut through complexity and disorient us at the same time. No wonder our legends teem with mirrors. Think of vampires, fun houses, bad luck, the infinite regress of self in the barber shop, and the face of Medusa.

Perhaps that's what the seventeenth-century mystic, George Herbert, meant when he said, "The best mirror is an old friend." For old friendships invariably prove to be just as dear -- and just as subtly complex and puzzling -- as that seemingly simple mirror we look into, first thing every morning.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

For more on chiral molecules see Episode 604 and Episode 1181.

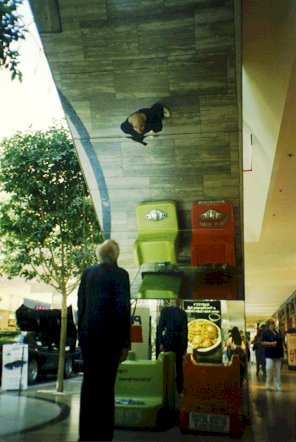

Photo by Carol Lienhard