A Better Mousetrap

Today, let's build a better mousetrap. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Build a better mousetrap, and the world will beat a path to your door, Emerson supposedly wrote. But writer Jack Hope finds what Emerson really wrote: "If a man has good corn, or wood, or boards, or pigs, to sell ... you will find a broad hard-beaten road to his house." [1] Nothing there about mousetraps. In 1889, seven years after Emerson died, someone quoted him as having said, "If a man can write a better book, preach a better sermon, or make a better mousetrap than his neighbor ..." and so on.

Emerson meant that quality prevails in the marketplace, and that comes to light in an odd way with the history of mousetraps. We've made a vast investment of ingenuity in them. By now the Patent Office has issued over 4400 mousetrap patents. Yet only twenty or so of those patents have ever made any money.

Today some 400 people still apply for mousetrap patents each year. That leaves me to wonder whether mousetraps really promise a fast track to inventive success, or if they're simply born of some morbid fascination with killing mice.

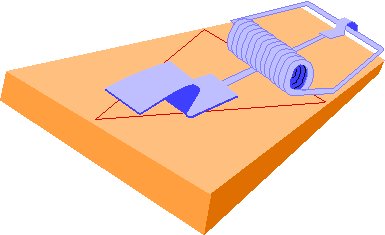

Actually, the mousetrap problem was solved in 1899 by one John Mast of Lititz, Pennsylvania. Mast filed for a patent on his now-familiar snap-trap. A heavy spring-steel wire swings down and breaks the mouse's neck when he nibbles cheese on the trigger mechanism. That was only ten years after the mousetrap quotation became common currency. The inventive muse (or maybe the inventive mouse!) keeps generating mousetrap patents, but none has yet beaten the snap-trap in the marketplace. No one has really built a better mousetrap.

Before (and after) Mast, inventors cooked up an unending series of gadgets for mashing, cutting, and maiming mice -- for drowning them -- for catching them alive. Early in the 20th century, people tried electrocution. The problem is, an electrocuted mouse continues to fry until someone smells the mess.

In the end, esthetics and mercy are twin factors that've strongly determined what the public will and will not use. In the 1980s, a superglue trap came out. It worked, but homeowners found themselves faced with a screaming mouse, still living, glued to a piece of sticky cardboard, dying of exhaustion. If mice have to be killed, most people can deal with a quickly broken neck. The more gruesome stuff won't sell in the long run.

And when snap-trap makers found most people throwing the trap out with the mouse, not even trying to disengage it, they followed the public's lead and began advertising snap-traps as "disposable."

So while the mousetrap has become an icon for inventive creativity, the public eventually stipulates what's acceptable and what is not -- in the grisly business of holding a competing species at bay.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

1. Hope, J., A Better Mousetrap. American Heritage, October 1996, pp. 90-97.

Clipart

The Conventional Snap Trap