Seaplanes

Today, we ask what became of flying boats. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The problem of finding clear space for takeoffs and landings dogged airplane builders from the start. Several people tried to use water instead of land, even before the Wright brothers; and they took off from a pair of rails. The first person who actually flew off water was Henri Fabre. In 1910, he flew his flimsy seaplane for a mile and a half in a harbor near Marseilles.

Three years later the first commercial flying service was started, and it used an early seaplane. Twice a day it made the 20-mile flight between Tampa and St. Petersburg in Florida. There was only one passenger, and the trip cost him five dollars.

Twenty years later, commercial flying boats were the biggest things in the sky. It felt safe to cross the ocean in a flying boat, and that's where they were used. Pan American began service down to Central America with a 10-passenger Sikorsky seaplane in 1928. By 1934 these seaplanes were being replaced with big flying boats, like the Martin M-130. It had a 3000-mile range and could carry 40 people.

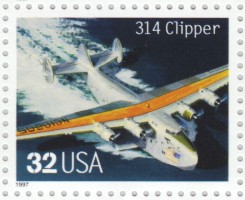

The grandest of the successful flying boats was the Boeing 314, nicknamed the Yankee Clipper. Pan American used them between 1941 and '46. It had almost the wingspan of a 747, and it could carry 70 people over 4000 miles.

Several perfectly enormous flying boats were built after the Yankee Clipper, but they came at the wrong time. The biggest of them all was the Hughes Hercules -- better known as the Spruce Goose. Its wingspan was half again that of a 747, and it was designed to carry 700 people. In 1947 Howard Hughes flew it 30 feet into the air over Los Angeles Harbor. Then he put it back in its hangar, where it sits today -- in mute and perplexing testimony to his convoluted thinking.

But I wonder if Howard Hughes didn't simply see what was coming. When big propeller-driven airliners, and then jets, came into service after WW-II, seaplanes lost their advantage. These land-based planes could fly the ocean, and there was no profit in using one kind of airplane over water and another over land. Furthermore, seaplanes where inherently large-bodied, high winged machines -- ill-suited to near-sonic speeds. Of course, their large bodies made them wonderfully spacious. They typically had two- or three-story interiors. They looked not unlike whales.

Little seaplanes are used today in Canada and Alaska, where lakes are a lot easier to find than landing strips. But the big flying boats had a rather brief day in the sun. And the last of them represented a terrible misreading of the way the technology of flight was actually headed.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Angelucci, E., World Encyclopedia of Civil Aircraft. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1982, Chapter 1.

This episode has been greatly revised as Episode 1578.

The Pan American Clipper

(clipart)

Howard Hugh's Spruce Goose at the apogee of its only flight