An Old Book of Recipes

Today, a book tells how our great-grandparents did things. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

So much of what we now buy in drug and hardware stores we made for ourselves in 1895. Just how much, I hadn't realized until I found an offbeat old book: Lee's Priceless Recipes. Don't let the title fool you. It isn't about cooking supper.

This compact compendium runs over 300 pages -- some 3000 formulas for everything you can imagine. It has sections on The Household, The Druggist, Toilet Articles, The Chemist and more.

The Druggist section begins with recipes for antacids. It goes on to liniments and ointments. It explains how to mix your own tincture of opium. The book tells how to replicate many popular patent medicines -- liberally laced with arsenic, carbolic acid, alcohol, and hemlock, as well as sarsaparilla, aloe, myrrh, frankincense, and digitalis.

The toiletries section offers recipes for perfumed waters, rouge, and lipstick. Lipstick is made from cold cream, wax, and a little carmine of vermilion. To remove wrinkles we mix a scruple of aluminum sulfate with a half-pint of water and use it to bathe our face three times a day -- I think I'll live with my wrinkles.

By the way, a scruple is an old word meaning a small part of an angle, a weight, or an hour. Here it means a 24th of an ounce. Scruple comes from the Latin for a rough pebble. So it also means a nagging pebble in the shoe of our conscience. Weights and measures weren't standardized a century ago. The book groans with drams, pennyweights, grains, and various kinds of pounds.

We see how to mix paint and paint removers, how to slice steers into beef steak, how to make ink, how to etch copper, how to make pencil leads, and how to turn crude suet into oleomargarine.

One item especially catches my eye. It's a prescription for killing tobacco worms. No arsenic or carbolic acid here. Rather, the book recommends a biological counterattack. The solution is to turn four-winged flies upon the worms.

There's a long section on making explosives: gunpowder, fulminate of mercury, nitroglycerin. It tells how to make dynamite from nitroglycerin. Then it blandly warns that dynamite is set off by simple percussion. If that sounds frightening, well, I used to make gunpowder by their recipe when I was a kid. The fact I'm here to tell about it probably testifies to my ineptitude.

I'm powerfully struck by how in touch with physical processes our forebears were. Take their recipe for ice cream. It's the same ice cream my great aunt used to make for me. Two quarts of thick cream, the yolks of three eggs, a pound of sugar -- need I go on! But people really did do much of this stuff for themselves. That was just ending when I was a child. And today -- this little book seems to represent life on another planet.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Oliver, N.T., Lee's Priceless Recipes. Chicago: Laird & Lee Publishers, 1895. (I am grateful to Detering Book Gallery in Houston for turning up this odd little relic of yesteryear.)

See also a much older book of this type which may be found in the UH Library: Mackenzie's Five Thousand Receipts in all the Useful and Domestic Arts: ... Philadelphia: James K. Jun and Brother. 1829. (Author given as a "An American Physician")

The title page of Lee's Priceless Recipes, 1895

Image courtesy of Special Collections, UH Library

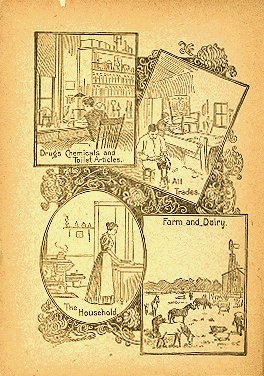

The frontispiece of Lee's Priceless Recipes, 1895

Image courtesy of Special Collections, UH Library

Here's a recipe for you. Do not try this at home!

Image courtesy of Special Collections, UH Library

Another work of this type is Mackenzie's Five Thousand Receipts in all the Useful and Domestic Arts: ... Philadelphia: James K. Jun and Brother. 1829. (Author given as "An American Physician.")