A Conservation Lab

Today, we ask: Just what is a conservator conserving? The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Jack Thompson greets me at the street-level door of an old warehouse just north of downtown Portland, Oregon. We ride the freight elevator to the third floor and enter his wing of the building -- maybe 5000 square feet of highly organized clutter.

He calls it a conservation laboratory. I'd been unsure just what Thompson conserved -- books, paper? So we start out.

He shows me photos of a 14th-century manuscript book he recently rebuilt. "Look," he says, "it's a schoolbook. People were dying of the plague all around this man, and he had enough hope for the future to write a grammar text for children."

A clamp holds gatherings of pages for another old book so he can sew them together. A stack of quarter-inch oak boards will be used to make the covers. He's been splitting the oak in stages and drying it for five years. He's cleaned, soaked, dehaired, limed, and softened animal skins to wrap the boards.

He has a library of old books on the old arts. Modern books about these techniques aren't too helpful. They say inks were once made from materials like oak gall and linseed oil. But what is oak gall? I ask him. He reaches into a bag of oak galls and hands me one. It's a parasitic growth on an oak tree -- rich in tannic acid. "And here's a linseed pod," he adds, giving me one.

Thompson runs a camp in Idaho. Each year he takes a group into the forest to learn the old crafts. They make paper from pulp pounded to slurry in a mill driven by a water wheel. They make ink, bind books, clean and soften hides to make parchment.

A ruined fire hose hangs in the corner of the lab. It seems fire hoses were once made of linen. Linen fiber makes superb paper. He shreds the hose and feeds the bits into his water-driven mill. I take away a sheet of paper made from a cast-off fire hose.

Here's a small pile of blue stones -- lapis lazuli tailings from a jeweler. Thompson grinds them up and runs them through complex chemical processes. The result is genuine ultramarine pigment. "This stuff costs $2000 an ounce on the market," he says.

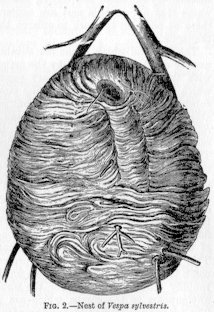

He shows me paper marbling, leather embossing, tapa fabric, mulberry paper, and wasp paper. "Did you know wasps taught us how to make paper from wood?" he asks. I didn't.

Suddenly I know that I know nothing. The 20th century has given me much, but it's taken as much away. I'd wondered just what Thompson is conserving. Now I know. Book repairs are only the vehicle. What he really preserves is the one thing without which old books, and much more, will die off. He's conserving the very arts by which we lived our lives -- until just this century.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

I am very grateful to Jack Thompson, Thompson Conservation Laboratory, 1417 NW Everett, Portland, Oregon, for spending a morning with me and generously helping me to understand these almost-lost processes.

For more on the problem of preserving old technologies, see Episodes 271 and 1048. For more on early paper, see Episodes 894, 1052, and 1227.

Two typical kinds of oak galls used in making inks

From the 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica

From the 1897 Encyclopaedia Britannica