Whitman's Butterfly

Today, a butterfly is not what it seems to be. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

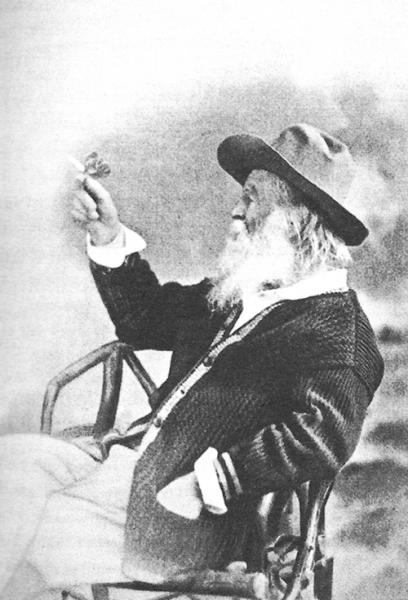

A now-famous photo from the 1883 Miami Herald shows white-bearded Walt Whitman with a butterfly landing on his hand. He looks like some latter-day St. Francis -- a child of nature.

But there's more to that butterfly: In 1942, right after we went to war, the Library of Congress shipped its most precious holdings inland. The Declaration of Independence went to Fort Knox. A crate with ten of Whitman's notebooks in it went to Ohio.

When the crate came back in 1944, the notebooks were gone. Lost or stolen? We don't know. Fifty years later, in 1994, a young man turned up at Sotheby's Auction Gallery with four of the notebooks from his father's estate. As soon as he learned their history, he returned them without claiming any of their half-million-dollar value. And we had a new window into Walt Whitman.

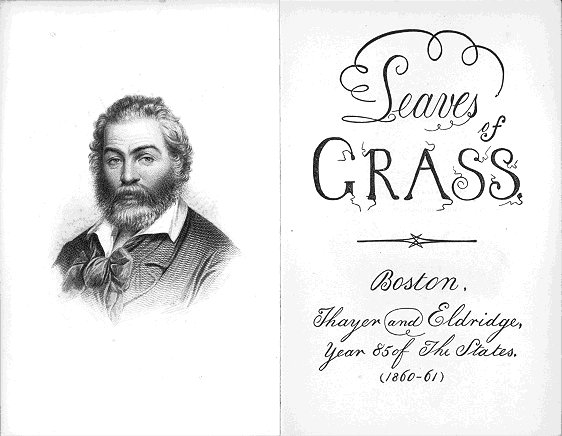

Here were draft portions of his epic poem, Leaves of Grass. Young Whitman described his work as a nurse in a Civil War hospital. That part gives us a very human picture of Whitman. He wrote letters for men who couldn't write, and he recorded their deaths. He talked about requests from the wounded and dying -- for an orange -- even for a piece of horehound candy.

Then a real bombshell: In one notebook, we find a butterfly, drawn on paper and carefully cut out. It's the same butterfly as in that 1883 newspaper. So much for St. Francis! The butterfly was a fake. Whitman was manufacturing his own image.

But wait! Genius often walks three steps ahead of us. Everything about Whitman was a composition. He was a part of the picture he drew. The problem of matching appearance and reality, says author Miles Orvell, obsessed him.

Poet! beware [Whitman says] lest your poems are made in the spirit that comes from the study of pictures of things, [and not from] contact with real things themselves.

So Whitman used the new cameras to make himself part of the poem. His own image became a dimension of his self-expression. He didn't put his name on the title page of Leaves of Grass, he put his photo there -- standing in rough clothes, the image of action, the image of the America he was writing about.

We all do that, of course. We offer a face to the world -- strong, caring, reckless, intellectual, sinister. We all try to do what Whitman succeeded in doing. In the end, that fake butterfly doesn't tarnish the poet at all; it explains him.

Whitman's poetry was visual art. It was theater. Poetry was a process where he struggled to be one-and-the-same with the face he showed to the world. That's surely the hardest thing any of us ever does. We try to decide whether we're gentle or tough, while the real butterflies circle -- always outside our reach.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Missing Whitman Papers Surface after 53 Years. The Manuscript Society News (Steve L. Carson, ed.), Vol. XVI, No. 2, Spring 1995, pp. 45-48.

Orvell, M., Whitman's Transformed Eye. The Real Thing: Imitation and Authenticity in American Culture, 1880-1940. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1989, Chapter 1.

Whitman, W., Leaves of Grass. New York: Doubleday, Doran & Co., Inc., 1940.

I am grateful to Pat Bozeman, Head of Special Collections at the UH Library, for providing the article on Whitman's missing notebooks and suggesting it might be story worth sharing.

For more on Whitman and his sense of iconography, see Episode 342

Image courtesy of Special Collections, UH Library