Forgery

Today, a cyclotron warns us not to overspecialize. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Tony Bliss, a librarian at Berkeley, shows me a paper he's written. It tells a story about a manuscript book. The Latin inscription at the end of the book says it was written in 1328.

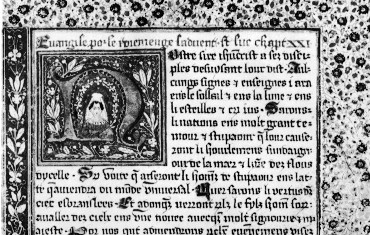

Before Gutenberg, before the plague, before the horrors of the Hundred Years' War, this text (it seems) was written out in a peculiar Gothic hand on now-yellowed parchment -- a set of Gospel readings in an odd French dialect, one for each Sunday of a year.

Yet something about it is wrong. The inscription has features that are out of place in medieval Latin. A gold initial letter holds a miniature portrait of a lady. She's too realistic for medieval imagery. So scholars begin questioning details.

Linguists offer theories for the anachronistic Latin. Historians look for the source of the French text. Meanwhile, Bliss does the most startling thing of all. He takes the book up to Davis, California, where the University has an old cyclotron.

This decades-old machine has long since been surpassed by bevatrons and linear accelerators. Now it's found a new kind of service -- the non-destructive analysis of paper and inks.

Here's how it works: When high-energy protons strike atoms of the heavier elements, each element emits a distinct X-ray pattern. When protons strike ancient papyrus texts, we get nothing at all. The organic papyrus and the ink are made of light elements: carbon, hydrogen, oxygen. But medieval texts are another story. They have metallic elements in them. They make the output of the cyclotron light up like a Christmas tree.

So Bliss presents his book to the cyclotron. The parchment shows heavy concentrations of calcium, white lead, and iron oxide. That's not the makeup of animal skin, but of early-20th-century clay-finished paper -- with a yellowing agent to make it look old. The story gets worse. The gold foil in that ornate initial letter was made from powdered brass.

What many people suspected suddenly becomes obvious. This is not just a fake. It's a clumsy fake -- maybe from a 1920s Italian cottage industry in counterfeit books. "Now," Bliss says to me, "Look what happened! Linguists were fooled; art and language historians were fooled. How do you suppose that could happen?"

Of course, highly specialized people are vulnerable. When one expert fails to see the other parts of the fake, his own part becomes an interesting anomaly -- something to be explained.

This is more than just a delicious mix of old and new. The cyclotron reminds us that we must see more of the elephant than its trunk, tusk, or tail. It makes a fine metaphor for the failure of overspecialization -- which is the real culprit in this story.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Bliss, A.S., Cyclotron Analysis and a Fake Gospel Lectionary of 1328. SCRIPTORIUM: International Review of Manuscript Studies, Tome XXXVIII, No. 2, 1984, pp. 322-325.

The "inscription at the end of the book" mentioned in the episode is actually a colophon. A medieval colophon included the title and imprint information which we find in the front of printed books today. I am grateful to Anthony S. Bliss for his counsel on this episode.

A page of the fake Gospel Lectionary

Image reproduced courtesy of The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley