Of Balloons and Computers

Today, messages from computers and a message from a balloon. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

A local grade school sent me a joyous cluster of balloons after my thousandth episode. What a lovely gesture! For seven weeks, balloons swayed under the ceiling fan. Each time I saw them they touched me. They reminded me what powerful role-models for change and adaptability school children are.

A local grade school sent me a joyous cluster of balloons after my thousandth episode. What a lovely gesture! For seven weeks, balloons swayed under the ceiling fan. Each time I saw them they touched me. They reminded me what powerful role-models for change and adaptability school children are.

I thought about those children and their balloons yesterday while I was talking with a friend about change and adaptability -- about the new computer networks. She said she didn't need the networks, even though she knew she would, eventually, use them.

"But, but, but," I sputtered. "The networks are restitching our broken world. They bind us together in times that seem to be blowing us apart. The networks give us new ways to talk to one another, just when conversation seems to grow impossible."

She looked at me as though I were selling snake-oil. After all, she hadn't experienced what I had. How could I make sense? So I thought about children and balloons -- what it was to be seven years old: Math means nothing. Literature means nothing. Life is a clean slate. All meanings have to be forged from scratch.

My friend was right, of course. No one needs a new technology. We can't feel any need for things we've never experienced. We jitter about this new medium, wondering whether we want to accept the terrifying gift of change. Some of us will let it transform us. For the rest, life will go on. But, in the end, I know my friend will be among those who do accept the gift.

The need for transformation is something that lies at our biological core. On some level we have to have it as surely as we have to have air. Once we called ourselves Homo sapiens, they-who-are-wise. Now we use the term Homo technologicus, they-who-use-technology. Actually, we're Homo transformandus, they-who-undergo-transformation. We create technologies, then we let them transform us. That's who we are.

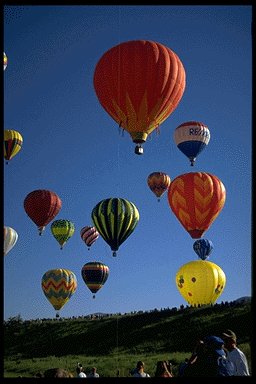

By now, of course, all but one of my balloons had finally sagged to the floor -- one with the word "Congratulations" written on it. So I released that last silver balloon into the sky. The message rode away on the south wind 'til it was only a dot.

Then it vanished from sight, but that invisible balloon kept on catching bright flashes of sun -- telegraphing one more unexpected message of joy and hope back to me -- reminding me what the children knew, and what they wanted me to know. I watched that balloon flashing its Promethean message, stealing fire from the sun and promising change -- promising unwanted and indispensible change.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

I'm grateful to many people for pieces of this episode. I'll name just two: Nora Walsh of Douglas Elementary School, who sent the balloons on behalf of her students. (My radio station, KUHF, enjoys a special relationship with Douglas Elementary.) And Jeff Fadell, UH Library, who crafted the term Homo transformandus.