The Golden Spike

Today, an engineer warns us there will be no more West. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

May 10, 1869: the place, northern Utah, the same place my great-grandpa came out of the Wasatch mountains less than 23 years earlier. He was walking to California, with his supplies on an ox cart. Officials are driving a golden spike to join rail lines from Omaha and San Francisco. All four of my grandparents were alive the day that spike was driven. It was that recent.

Now passengers could buy a ticket all the way from Omaha to Sacramento for $111. A trip that took great-grandpa all summer, and put him deeply in debt, could suddenly be made in 4½ days.

Congress had authorized the new transcontinental railway during the Civil War. Historian Maury Klein tells about an engineer surveying the route in 1868. He wrote in his diary,

The time is coming, and fast, too, when in the sense it is now understood, THERE WILL BE NO WEST.

When railway crews followed, they pushed through the forbidding dry highlands west of Laramie as fast as they could. One crew boss wrote, "This is an awfull place, alkalai dust knee deep and certainly the meanest place I have ever been in."

Great-grandpa almost died of thirst when he crossed that stretch. He desperately needed to go for water, but he had to protect a pile of freshly killed buffalo meat from a lurking wolf. And that was just a few days after he'd passed the ill-fated Donner party along the Platte River. They would soon be snowed in, and starving to death, in the Sierra mountains.

That was 1846. Now, in 1869, track was being laid and George Pullman was selling hotel trains to the railway companies -- trains with sleepers, diners, and drawing rooms. Now railways wouldn't have to stop to feed their passengers. You could get all the way from New York to San Francisco in only 5½ days.

The engineers did a fine job plotting a course through that wilderness. The route had no grades over 90 feet per mile. In a major overhaul 30 years later, the Union Pacific hardly changed the original roadbed. Good thing they didn't! The railways had planted towns along the tracks to pick up farm produce. They named them after baseball players and European cities.

So the buffalo and prairie wolves disappeared. And great-grandpa? Well, he didn't wait for the trains to come. His adventure was over long before that. He looked around in 1850 and felt the West was already gone. He went back to Switzerland.

It was that quick. And I have to remind myself, in the classroom, that I'm talking to students who've never seen a steam locomotive -- nor, for that matter, harnessed an ox or eaten meat they've hunted. I have to remind myself that there really is no more West.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

American Heritage of Invention & Technology, Vol. 10, No. 3, Winter 1995. See especially: Klein, M., The Coming of the Railroad and the End of the Great West, pp. 8-17; and Razilowski, J., Same Town, Different Name, pp. 20-21.

Lienhard, H., From St. Louis to Sutter's Fort, 1846 (tr. and ed. by E.G. and E.K. Gudde). Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1961.

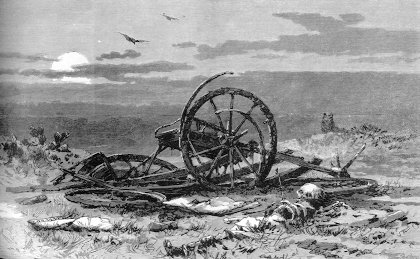

Image of the overland crossing before rail

From the 1881 Harper's Weekly

Driving the Golden Spike

From How we Built the Union Pacific Railway, 1910

An 1868 brochure on the yet-to-be-completed transcontinental railroad

Image courtesy of Special Collections, UH Library