Charles Lindbergh lived only to the age of 72. But that was long enough to bring him through the early days of flight, through war and aerial combat, and into the wholly changed world of the latter 20th century. Not long before he died in 1974, Lindbergh wrote the foreword for a book about a native Philippine tribe and his words are hardly those of the hero/adventurer that his name calls to mind. He said:

Charles Lindbergh lived only to the age of 72. But that was long enough to bring him through the early days of flight, through war and aerial combat, and into the wholly changed world of the latter 20th century. Not long before he died in 1974, Lindbergh wrote the foreword for a book about a native Philippine tribe and his words are hardly those of the hero/adventurer that his name calls to mind. He said:

During decades of [flying we crowded ourselves into] cities that spread like scabs across the landscape. Obviously an exponential breakdown in our environment was taking place; and, just as obviously, my profession of aviation was a major factor in that breakdown. Aviation had opened every spot on earth to exploitation.

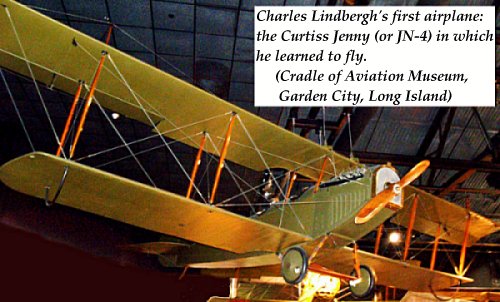

Lindbergh had been raised in a small Minnesota town. His father was a progressive congressman, his mother a chemist. It was she who drew him into technology. Lindbergh studied some engineering, but didn't have the patience for it. He dropped out and enrolled in flying school.

For a while he barnstormed, and, before he was twenty, he began eyeing the $25,000 Orteig prize offered to the first person who could fly nonstop and solo, from New York to Paris. In 1927, of course, he won the prize and the fame that went with it.

By the mid-‘30s he was consulting in Nazi Germany. Hitler's technocracy impressed him, even if he distrusted Hitler’s politics. Back in America, he preached defensive isolationism. When war began, he offered his services to the Army who, by then, saw him as pro-Nazi. They refused to take him. So Lindbergh went to industry. First he helped Ford make B-24 bombers. Later, he was almost killed test-flying a P-47 for Republic Aircraft.

We find him, at age 42, working as a "civilian" test pilot in the South Pacific -- testing P-38s and Corsairs in actual combat. He flew some fifty bombing and strafing missions and even shot down one Japanese plane. His work changed the tactics of low-altitude combat. During his 36th mission, he found himself in the sights of a Japanese Zero. He wrote,

I can see the cylinders of the Zero’s engines, feel its machine guns rising into line behind me. It is too close to miss. I pull my elbows inside the armor plate and brace for the impact of the shells.

Moments later, another plane saved him. But this was no longer the voice of a barnstormer; it was the voice of an authentic war hero for whom life had become precious.

Lindbergh went on to influence the development of civilian jets. But he also wrote. He expressed the conflict he saw rising between the benefits and the dangers of modern technology. Then, in 1955, his wife Anne wrote Gift from the Sea. She contrasted a simple life on the seashore with, in her words, "the curtain of mechanization [coming] down between the mind and the hand."

Did Charles read that as criticism of a life spent pushing the machine ahead of its human users? Perhaps. In any case, he became less publically visible. He worked with quiet intensity trying to implement sane environmental policies. He pushed for the creation of the Congressional Office of Technological Assessment.

He ended his long and complex life with a deep commitment to the ground -- below the sky. I find his recollection of a prewar visit to the ninth-century Chapel of St. Gildas on an island off the coast of Brittany very poignant. First, he writes,

A decade before, when I was flying from America to Europe in my Spirit of St. Louis, I had looked down on the Atlantic and wondered what shapes and contours were masked by the sameness of its surface. ... the sea maintained its dignified aloofness.

But, as he walked the beach below, eleven years later, he saw a much different place. He says:

At the edge of Saint-Gildas, each fastly ebbing tide opened the ocean’s threshold, let you step into a strange and foreign realm. Fish, camouflaged by weeds, hung motionless in crystal pools. Green, protoplasmic masses lay inertly on the stones. A tentacle from a small squid flashed out.

The game had changed. No more barnstorming. After our world had erupted in total war for a second time, we emerged seeing it through different eyes. Lindbergh was a boy no more. He’d been reshaped by the powerful forces that’d pulled us into a different orbit. Perhaps our generation, more than others, cried out for realignment in the 1950s.

With that in mind, let us go to another flier/writer who made that same transition -- that same leap away from the old world to the new -- but who did so in a different way. Let us meet Nevil Shute.

Sources:

L. S. Reich, From the Spirit of St. Louis to the SST: Charles Lindbergh, Technology, and Environment. Technology and Culture, April 1995, Vol. 36, No. 2, pp. 351-393.

J. Nance,The Gentle Tasaday: A Stone Age People in the Philippine Rain Forest. Foreword by Charles A. Lindbergh (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975).

C. A. Lindbergh, Of Flight and Life. (New York: Charles Scribner’s sons, 1948.) pp. 10-14.

A. M. Lindbergh, Gift From the Sea. (New York: Pantheon Press, 1955.)

C. A. Lindbergh, Autobiography of Values. (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976) pp. 366-367.