Writer David McCullough once made an odd remark. So many early airplane pilots, he said, were physically attractive -- and they were writers. Generalizations like that put us off, of course. But look at some cases: Handsome Charles Lindbergh wrote many books in his later life. And his lovely wife, Anne Morrow Lindbergh (who also flew) created a whole body of litera-ture -- both about flight, and topics well beyond flight.

Writer David McCullough once made an odd remark. So many early airplane pilots, he said, were physically attractive -- and they were writers. Generalizations like that put us off, of course. But look at some cases: Handsome Charles Lindbergh wrote many books in his later life. And his lovely wife, Anne Morrow Lindbergh (who also flew) created a whole body of litera-ture -- both about flight, and topics well beyond flight.

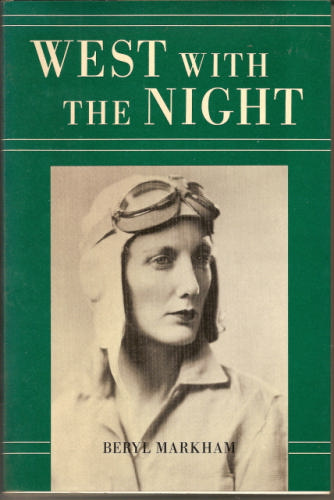

Saint-Exupéry was less to look at, but he could write! His book The Little Prince was a masterpiece of children's litera-ture. He and the Lindberghs were close friends -- drawn togeth-er by words as much as by flight. Anne pointed out that he was a better writer than a flier -- he crashed too often. Beryl Markham wrote only one book, West with the Night, but it was such fine writing. Listen as she tells about leaving Nairobi on a dreary morning in the 1930s:

[We] left at a pilot’s hour, but on no pilot’s day. Fog had spilled out of the sky by night and the morning found Nairobi and the Athi Plains bundled in mist. The town, the sunrise, and the [plane] were isolated each from the other by clouds that had no edges and re-fused to roll. They lay on the earth like sadness come to rest; they clung to people like burial clothes, white and premature ...

Was prose like that borne of literary genius or the experi-ence of flight? My images of flight were powerfully shaped by my father's story-telling. I would lie in bed while he made up tales laced with images of turning and wheeling among pillars of clouds -- tales of danger, fear, and walking away from crashed aeroplanes, of the smell of the engine's castor oil in an early morning takeoff. Then I notice a photo of my father in his WW-I flier's uniform and I realize: I’m looking at a handsome young man who went on to become a writer.

So they wrote: Nevil Shute wrote and Ernie Gann Wrote. Amelia Earhart wrote prose when she really wanted to write poet-ry. Saint-Exupéry wrote, "I saw the alchemy of perspective re-duce my world, and all my other life, to grains in a cup." Lindbergh said the airplane plunged him into the heart of the mystery of existence.

I think the airplane created the prose -- the airplane, born of our desire to fly -- a craving that came before technol-ogy, before language, almost before the womb. And the physical attractiveness? Maybe that echoes something Abe Lincoln said -- that, after a certain age, we bear responsibility for our face. Maybe these people simply accepted that responsibility. The two things merge when Saint-Exupéry describes a pilot on a night flight falling "into the deeply meditative mood of flight, mel-low with inexplicable hopes."

So let us meet some of these people. Perhaps, if get to know them more intimately, McCullough’s odd claim will make bet-ter sense: that a new technology, one so closely wedded to our most atavist craving, might drive the pen and shape the face to-gether.

As we do, we find something unexpected. It is that flight opened a whole new beauty -- a whole new way to see earth and sky. Flight demanded not only that we look with new eyes, but also that we express what we now saw in a wholly new voice.

Source:

McCullough, D., Brave Companions: Portraits in History. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992, Chapter 9.