Script for the Engines CD, Fall 2002

by John H. Lienhard

Mechanical Engineering Department

University of Houston

Houston, TX 77204-4006

jhl [at] uh.edu (jhl[at]uh[dot]edu)

Audio Production and sound mixing: Capella V. Tucker

Music: Andrew Lienhard Daydream4 Productions

Voices of Lucy and Adam: Carol and John Lienhard

CD Production: Greg Johnson

For a Stone Age Timeline, click here.

Source material is given at the end of this text.

Track 1: Introduction (1:10): Call me Adam. It's as good a name as any. And my mate here -- you can call her Lucy. She and I are very old. We've traveled time together over four million years. Now we want you to join us in our travels.

[Lucy] We'd like to show you some of the things we've seen over the aeons. We especially want to show you some of the fine invention we've seen along the way. We want to talk about a time before we'd learned to set our accomplishments down on papyrus or paper. We ask you to join us on a trip through the wonderful, underrated Stone Age.

The last track on this CD is only data. It won't play in your audio player. But when you put the CD in your computer, you'll be led to the full text, along with images, links, and sources. We recommend you do that. But right now, we begin at the beginning, using only the spoken word to tell about times before there were any written words. Much of what we visit here took place before Lucy and I had even speech to tell about the things we did.

Track 2: A Radiator for the Brain (3:30): Lucy and I no longer walk the hard earth today. And we weren't much to see when we first walked present-day Ethiopia, just over four million years ago. Back then, we were less than four feet tall.

Anthropologists now call us Australopithecus. That word makes no attempt to summon up anything human. It literally means "Southern Ape." We'd only just learned how to walk on our hind legs, and our kinship with you hadn't gone too much beyond that. Our brains were about the same size as a chimpanzee's -- about a third the size of yours.

[Lucy] Adam, you should tell about paleontologist Dean Falk -- how she explains the evolution of our brains into what they are today. Her book, Brain Dance, shows how our brain might've been the key to the whole business.

Falk begins with the discovery of the first Australopithecus skull in South Africa in 1924. In those days, paleontologists avoided controversy with anti-evolutionists by classifying anything that might have been our ancestor as human. In fact, that's how one of the major anti-evolution myths grew up -- the myth that we've never found the missing link. Lucy and I were that link, but nobody was about to say so out loud.

In any case, Falk found structures in Australopithecus's brain that were apelike, not human. For more than two million years, Lucy and I walked upright, with our hands free, yet our brains remained those of an ape.

Then, about two million years ago, our brains began growing. They took on the kinds of folds and creases that your brain has today. A species called Homo habilis emerged with a forty-percent-larger brain. By one and a half million years ago, another species, Homo Erectus, had evolved and it was walking the hot plains of Central Africa with a brain more than double the size of Australopithecus's -- although Lucy and I were still around in our original Australopithecus form.

Left: Australopithecus, or Lucy/Adam. Right: Homo Habilis

Reconstructions at the University of New Mexico Anthropology Museum

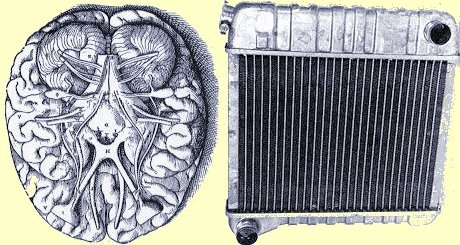

Falk struggled to understand what'd happened. Then, something emerged from her subconscious. One day her car mechanic had told her, "The size of your car's engine is limited by the capacity of its radiator to cool it." That was it! The brain is terribly sensitive to changes in temperature. It absolutely must be cooled in summer and heated in winter. But where is its radiator? Falk began studying the blood supply to ancient brains.

Sure enough: along with changes in brain size ran an evolving blood delivery system. When Lucy and I took to our hind legs, our heads had to bear the brunt of the African sun, and we began changing, very slowly. More holes appeared within humanoid skulls to provide access for more blood to cool the brain. The radiator of a Model-T evolved into the radiator of your Rolls-Royce brain.

It was 150,000 years ago that our brains reached their full modern size in, of all people, the Neanderthals. They began creating art, building huts, burying their dead, and worshipping deities. They weren't toilet trained, it seems, but then (if you look at our lakes and rivers) maybe we aren't either. However, now we had our radiator and now the real fun could begin.

Track 3: Making Silent Stones Speak (3:25): We've all heard it said that we humans are defined by our tool-making. So let me put a question to you. What were our first tools? The matter can very quickly grow confusing.

Chimpanzees, even birds, not only select branches and twigs for use as tools, they shape them as well. Tool-making, by itself, is not enough to set us apart. We need to ask if something about our tool-making sets us aside from other animals. Anthropologists Kathy Schick's and Nicholas Toth's book Making Silent Stones Speak, offers an answer. They remind us that, when Lucy and I first stood up on the plains of East Africa, we did no better than our four-footed ape cousins. And, as we saw in Track 2, we didn't evolve into a large-brained species until about two million years ago.

It was just before that evolution, about 2.4 million years ago, that our Homo Habilis progeny first began shaping stone implements. It is those tools that mark our departure from other apes. Those tools mark us as tool-makers.

It was just before that evolution, about 2.4 million years ago, that our Homo Habilis progeny first began shaping stone implements. It is those tools that mark our departure from other apes. Those tools mark us as tool-makers.

If we are to understand what we became, we need to go back and look closely at those crude stones. It takes a trained eye to see those ancient artifacts as tools. No delicate arrow-heads or harpoons here. No recognizable tools of any kind. These are hardly more than rocks with pieces chipped out of them. What were they used for -- scraping, hammering?

So scholars take to the forest to see how such tools might've been used. Photos show anthropologists flaying meat from dead animals, separating bones, sharpening sticks and scraping hides. Gradually they learn what our two-million-year-old ancestors did with each type of tool. As they do, the sophistication of those chipped rocks becomes clear.

And what about the stone tool as weapon? Who can forget the first scene in the movie 2001? For Stanley Kubrick, we became human when apes on some antediluvian desert found they could use a bone to kill other apes.

[Lucy] The fact is, anthropologists find little ancient evidence of manufactured stone weapons -- or of early bones being used as tools, for that matter. The stone-age Cain may've slain Abel, but you and I used these new technologies for far better things than fratricide. Anthropologists show how the earliest stone tools did what other animals could do. Our digging sticks copied an aardvark's digging feet. Our meat scrapers imitated a saber-toothed tiger's flesh-cutting teeth, and so forth.

That replication of other animals is where we see our emergence as a single species capable of replicating the functions of other far more specialized creatures. Shaping stone, for all its seeming simplicity, was a huge departure for our species. When we really see how sophisticated it was, we're less surprised that larger brains followed after we had stone tools. As anthropologists take the trouble to experience the mind-expanding rush of recreating our earliest tools, they see why Lucy and I went on to become something so different from any other primate. And we'll find, in the next track, that it was Lucy who showed us the way ...

Track 4: The Throwing Madonna (4:03): Next, we want you to meet a very interesting character. We call her The Throwing Madonna. That's actually shorthand for one of the ways we became serious toolmakers. Of course this idea is a little speculative.

[Lucy] Well that's right. You and I have a problem here, Adam. We watched all this happening, and these modern scientists are just trying to figure it out. We'll cause trouble if we start talking about things we know, before they discover them.

What do you think we should do?

[Lucy] Well, you could get around it by telling our friends out there about that neat speculation neurobiologist William Calvin made.

And let them think about the idea! Okay, Calvin suggests that women were a strong force among prehistoric technologists. His ideas are based upon some inspired detective work. He begins with mothers and babies. The parent/child bond is powerful. Think about the house cat who climbs into your lap to purr. Outdoor cats don't do that. Cats who live with humans learn to mimic babies, and they lay a powerful claim to our affections. Nestling near the heart awakens a bond. The heart is in the center of the chest, but the left ventricle pulses loudest. A baby is happier on its mother's left arm, where it takes the greatest comfort from her beating heart.

And let them think about the idea! Okay, Calvin suggests that women were a strong force among prehistoric technologists. His ideas are based upon some inspired detective work. He begins with mothers and babies. The parent/child bond is powerful. Think about the house cat who climbs into your lap to purr. Outdoor cats don't do that. Cats who live with humans learn to mimic babies, and they lay a powerful claim to our affections. Nestling near the heart awakens a bond. The heart is in the center of the chest, but the left ventricle pulses loudest. A baby is happier on its mother's left arm, where it takes the greatest comfort from her beating heart.

Calvin thinks that's the reason why most of us are right-handed. A mother survived with a child on her left arm only if she could protect herself with the right. When Calvin gives us the term, The Throwing Madonna, he's referring to the mother who can throw a stone at a jackal while she's holding her child.

Now, what has this to do with technology? Calvin points out that for right-handedness to have much Darwinian value, prehistoric mothers had to be deeply involved in the manual skills of survival. They had to be hunters, tool-makers, and tool users.

Modern scientists can't go back and look at cavemen, but they can look at advanced apes. Sure enough, hunting is shared among male and female apes. Here's a case history: Primate biologists have studied Japanese macaque monkeys. In one test, the scientists scattered grain in the sand along a seashore. The monkeys needed to get at the grain. One female monkey made a remarkable mental leap. She was trying to separate grain from sand. In frustration, she flung a handful into the sea. The sand sank. Grain floated back to her. In no time, she'd formalized the procedure. The young apes were quickest to copy her. Some adult males never caught on.

Calvin goes further. African chimpanzees shape sticks to catch termites in anthills for supper. Females are far more creative and persistent at this technology. The same is true in selecting tools and inventing methods for cracking nuts. Why? He offers a compelling hypothesis. Maybe it's because the female of the species spends more time with the young. And the young teach creative freedom of the mind to the old.

Well, as I said, Lucy and I have our own knowledge of all this, for we have lived it. But we must keep that knowledge to ourselves. It's enough for us to point out that Calvin's imagery of the Throwing Madonna convincingly connects the bond between mother and child with the creative process. Something else we need to mention here: Lucy and I have often had to rediscover our own inventive muse.

[Lucy] I'll say we have, Adam.

We've gained it and lost it many times, but we've never managed to reclaim it without first laying aside some of the solid ground of adulthood and maturity.

This is a point we come back to in Track 6. But first, we need to see what happened to Lucy and me after we became Homo Erectus. Now we had stone tools, we had a pretty substantial brain, we'd moved beyond Africa, and we were ranging over the entire Eastern hemisphere.

Track 5: Zhoukoudian Cave (3:25): Let's go back for a moment to the way Lucy's and my brains began evolving only after we'd taken up rudimentary stone-tool-making.

We've always been driven in that way by our technologies. Our machines are a physical extension of our minds. We may've invented them and built them, but they nevertheless teach us, form us, and make us into something new. They tell us things that we didn't build into them.

But that symbiosis worked very slowly at first. It took half a million years for Lucy and me to catch up with our stone implements. Author Jean Kerisel, who writes about soil mechanics and foundations, gives us a wonderful example of this process when he takes us into Zhoukoudian Cave, twenty-five miles south of Beijing, China.

When we took the form of early Peking Man, we began living in and around the cave 560,000 years ago. It was then a large limestone karst formation. It had stalactites and stalagmites and a sloping floor that ended in water catch-basins. We used the cave for 230,000 years. The bottom gradually filled in with layer after layer of detritus, and the floor gradually rose. We broke away the stalactites and stalagmites; we extended the ceiling and walls. At one point, the central chamber was 450 feet wide.

Archaeologists have been sifting downward through the millennia within the cave since 1921. The earliest tools they've found are crude sandstone implements. Later, the tools became sharper and smaller and were made of harder stone. The later tools reflect some knowledge of splitting and shaping stone. We also showed some elementary sense of structural form as we expanded the size of the cave. We began to gain some understanding of arches and rounded vaults.

Yet that seems like little gain in a quarter-million years. Modern humans wonder how far ahead of dam-building beavers or hive-making honeybees we were. It would almost seem that you're watching instinct at work more than human invention as you have come to understand it today.

You ask so much more of your technology. You expect it to change, and you expect it to change you. That hardly happened in the quarter-million years we lived in and around that cave. Our technology was too sparse. Its critical mass was simply not enough to let us see its creative possibilities.

[Lucy] Silt, bones, and castoff tools filled up the floor. Eventually we had to go off to some other cave. We continued our almost static lives for hundreds of millennia more. That only changed the other day -- some thirty thousand years ago. Suddenly our tools opened our eyes to a stunning range of possibility. Suddenly, in a blink, our tools began changing us into a radically different species.

And that happened when technique became technology. It happened when we began connecting technique with the telling of it -- with the ology of technique. It happened when we developed a whole new dimension of self-expression and then linked self-expression to our techniques.

Track 6: Oldest Technology and Oldest Flute (8:24): (Transition Music 5) Once we recognize a technology as both a technique and the sharing of that technique, we need to ask what the oldest technology might've been. That question takes us to an interesting place indeed.

What are the old technologies? Farming came late in history. Before farming, settled herdsmen and gatherers made clothing, knives, tents, spears -- but so did nomads before them. When we go back very far indeed, we find picture painting and music. Some really magnificent cave paintings survive, along with evidence of rattles, drums, pipes, and shell trumpets. Even the Old Testament -- the chronology of the Hebrew tribes -- identifies musical-instrument-making as one of three technologies that arose in the seventh and eighth generations after Adam.

[Lucy] Some smart kids there, Adam!

[Adam] Lucy, we're talking about the Biblical Adam.

[Lucy] Oh, are we now?

In any case, music is clearly as old as any technology we can date. Couple that with the sure knowledge that whales sing, that the animal urge to make music precedes technology, and we offer you music-making as the oldest technology of all.

Societies with the least technology on Earth are all strongly tied to music. Australian aborigine culture was defined by its song, dance, musical instruments, and poetry. Music is the most accessible art, and, at the same time, the most sophisticated. In almost any age, or any society, music-making is every bit as complex as other technologies.

But our own experience tells us as much as archaeology does. Experience tells us that music is primal. It's not just a simple pleasure. A Shakespearean lady says,

[Lucy] I am never merry when I hear sweet sounds of music

[Adam] And her lover answers:

The reason is your spirits are attentive.

The man that hath no music in himself is fit for treason ...

And we know what he means. If we can't respond to art -- to music -- then something's missing. We are fit for treason. Music helps us understand the human lot. Music is as functional as any worthwhile technology. Its function is to put reality in terms that make sense. That means dramatizing what we see -- transmuting it into something more than what's obvious. Wallace Stevens wrote:

[Lucy] They said, "You have a blue guitar,

You do not play things as they are."

[Adam] The man replied, "Things as they are

Are changed upon the blue guitar."

The blue guitar -- music, or any art -- does change reality. It turns the human dilemma around until we see it in perspective. Sometimes it takes us through grief and pain to do that. It disturbs us at the same time it comforts us. But it serves such a fundamental human need. That's exactly why music-making is as primal a human technology as we have.

Now, a companion question to "What's the oldest technology?" Let's ask, "What, then, is the oldest musical instrument?" Now we have a question that chokes on its own ambiguities. Should we count the cave man drumming on a log? Should we count your dog, rhythmically thumping her tail on the wall? Is that instrumental music?

The question becomes useful only when we start looking for sophisticated music-making machines. After all, birds and whales were singing complex songs long before we humans walked the earth. As we move back in time we find four-thousand-year-old cuneiform tablets that describe a diatonic scale. But the written record soon runs out.

And the oldest artifacts have been a few one-note whistles made by the mesolithic modern humans of some twenty-five-thousand years ago. Then, in 1995, Slovenian archaeologist Ivan Turk made an astonishing discovery. Turk found a four-inch length of bone from the thigh of a cave bear -- pretty minor except for two things: First, this bone was roughly 55,000 years old. That was before modern humans appeared in Europe. It seems to've turned up among Neanderthal remains.

Bob Fink's representation of Turk's bone discovery

The real shock is what's been done to the bone. Two holes, each a third of an inch in diameter, have been reamed into it. On either end, the bone has been broken where there were two more holes. We find that four holes have been carefully cut into the bone, and they're not evenly spaced. The bone practically screams flute at us, and a sophisticated flute at that.

Musicologist Bob Fink, from Saskatoon, studies the scales these holes could've joined in producing. Since he has only a fragment of the whole bone, he has to juggle possibilities. However, the uneven spacing means that, if this was a flute, it was tuned in a scale with whole steps and half steps. It was based on a scale that fits natural harmonics, the way all diatonic scales do.

Fink measures hole spacings and he juggles the statistical probabilities of whole flute arrangements. He concludes, with near certainty, that this was a Neanderthal flute, tuned to either a harmonic or a melodic minor scale -- a sound that's Oriental to the Western ear -- or sad, or exotic -- a beautiful and haunting sound.

Up to now, anthropologists have debated whether or not the Neanderthals had speech. If they did, their range of sounds was certainly less than ours. But evidence does suggest that they buried their dead, protected their handicapped, and honored some deity. And now, we have evidence that they were music-makers as well.

When William Congreve wrote his famous line about music having charms to soothe the savage breast, he missed the point. For where you have music you no longer have savages. The cartoon brutishness of the Neanderthal was originally created by nineteenth-century racism. Neanderthals had to be less than we because they didn't look the same. We knew their brains were at least as large as ours, but we swept that under the rug. Now this bone flute has stirred up a huge debate among ethnomusicologists. Was it really a flute? Once more, Lucy and I were there when this bone was shaped, but we are bound to keep our confidences.

What we can tell you is that the genie of self-expression was now out of the bottle. Indeed, anthropologists have recently applied fancy new dating methods to finds made at a site on Zaire's Semliki River. They believe the dig is around 90,000 years old, and it's yielding complex harpoon heads carved from bone. These harpoons have the sophisticated, sweptback teeth we once expected to find only after you modern humans had established yourselves in Europe, some thirty or forty thousand years ago. But your African forebears had already begun the great surge of self-expressive technology far earlier. A new species was already on the march -- a species that we might well call Homo Technologicus (or They-Who-Make-Tools).

Anthropologists have now found evidence that suggests our Neanderthal cousins created images before modern humans did so much with picture painting in the caves of Altamira and Lescaux. They've found primitive bone carvings. Whether or not Bob Fink is correct in his analysis, he certainly could be correct. For the Neanderthals had come into their own blue guitar of self-expression.

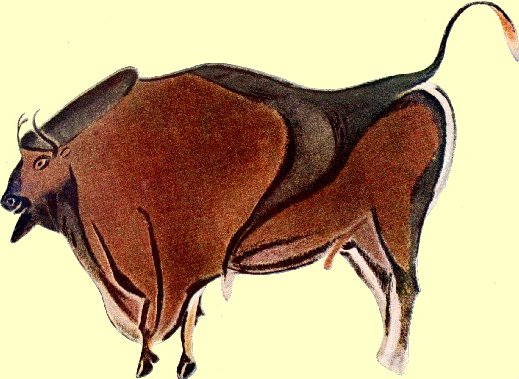

Facsimile of a palaeolithic painting of a bison in Spain's Altamira Cave

(from the 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica)

Track 7: The Dolni Vestonice Venus (2:57): I want you to meet a remarkable image of a lady. She cuts quite a figure with her 4-1/2-inch-tall fired-clay body, and with her exaggerated hips and breasts. She leaves no doubt that was to be the unmistakable image of woman.

Archaeologists call her the Dolni Vestonice Venus, after the Czechoslovakian site where they found her. Her 26,000-year age is astonishing. This Upper Paleolithic figurine is fourteen-thousand years older than the first ceramic pots and jars. She is part of the oldest known set of ceramic sculpture, and she was no isolated fluke. There were two kilns on this site, and they were surrounded by seven thousand fired ceramic fragments. Lucy and I weren't fooling around. We were seriously producing art objects.

We weren't yet very good at firing clay. We heated the objects to thirteen hundred degrees Fahrenheit, and most of them show thermal cracks. These ceramics probably had no practical purpose. They weren't made to last. What we're seeing is art for the moment. It is the strong expression of a few people who developed a technology for showing us what was in our minds.

These figures come from the so-called Gravettian period -- 28,000 to 22,000 years ago. By now, female figurines with the exaggerated sexual characteristics of the Dolni Vestonice Venus were widespread. But before this, Lucy and I had carved them all from bone, stone, and ivory. We'd never made them before from fired clay. By now, wherever we modern humans lived -- in Africa Europe, or Asia -- we left figurines like this. Now your archaeologists are struggling to learn whether or not we worshipped The Goddess in some form or another. Well, what we can tell you is that this lady was no local obsession.

The first cave painting had just preceded the great artistic outpouring of the Gravettian period. In the millennia that followed, an astonishing range of new techniques joined cave painting. These ceramics were only one of many Gravettian artistic experiments, and they weren't followed by better ceramics. Rather, they just died out with their makers. What did survive was the artistic impulse. Out of those artistic techniques eventually rose more utilitarian technologies.

When we look at these figurines we see an expanding human vision. My favorite is the head of a lioness. If the Venus caricatures woman, the lioness instead abstracts the quality of being a beast. The lion is coolly dreamlike and lovely. The two are quite different, but together they reveal the human imagination, poised at the door of a great mental leap forward.

Track 8: The Cloths of Heaven (4:06):

[Lucy] Here's a question to think about: When did people quit wearing animal skins and put on cloth? When did we invent woven fabric?

Well, Lucy, today's humans thought cloth was only seven thousand years old before they had carbon dating. Ever since then, they've been pushing that date back. In 1992, archaeologists found a half-fossilized scrap of cloth stuck to a piece of antler near the headwaters of the Tigris River. This one was nine thousand years old. Carbon dating has been doing that; it's been making all sorts of things older than anyone had thought they were.

This fragment of cloth shows up right along with the first agriculture. It was found on the site of a primitive farming community. These particular neolithic farmers had yet to make pottery. But they'd already learned to weave baskets.

When we see the community in context, we understand why they conceived a new material. The last ice age was retreating; weather was warming. As game moved north, people had to invent farming if they meant to keep eating.

So they looked at plants with new eyes. First they wove baskets from reeds and straw. Animal skins became harder to find and too hot to wear. They experimented with open meshes. They made skirts from leather cords.

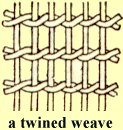

The Finns had already made open mesh fishing nets and carrying bags from woven plant fibers. But cloth is more complex. These ancient farmers had to learn to spin thread from flax. They invented tight weaves to replace open mesh.

This 9000-year-old fragment of linen is not simple. It's already a twined weave, a double weft laid on a single warp. It was by no means the first piece of cloth these people had made. And what was the article they'd made from this magical new material? What'd this bit of cloth now stuck to an antler once been? A cloth bag to collect bones for carving or for arrowheads? We can only guess. It was certainly one more harbinger of civilization rising out of the new practice of agriculture.

This 9000-year-old fragment of linen is not simple. It's already a twined weave, a double weft laid on a single warp. It was by no means the first piece of cloth these people had made. And what was the article they'd made from this magical new material? What'd this bit of cloth now stuck to an antler once been? A cloth bag to collect bones for carving or for arrowheads? We can only guess. It was certainly one more harbinger of civilization rising out of the new practice of agriculture.

So cloth became as sure an icon of beauty and wealth as gold. We dressed it in increasing color and complexity. As I weigh this ancient wounded fragment of human invention, I suddenly see why Yeats was moved to write:

Had I the heaven's embroidered cloths,

Enwrought with golden and silver light, ...

I would spread the cloths under your feet;

But I, being poor, have only my dreams;

I have spread my dreams under your feet;

Tread softly, ...

Now, let's go back to that Dolni Vestonice site we looked at in Track 7. As scholars picked over those shards of ceramic, they made a stunning discovery in 1995. One of the 26,000-year-old fragments, when it had still been wet clay, had been wrapped in what appears to have been cloth. There, clear as yesterday, is the imprint of woven fabric. You can make out the precise weave of the fabric.

This fragment is three times as old as the Turkish cloth fragment. Until recently archaeologists had thought that simple art and tool-making had just begun at this point. We took it for granted that such a complex invention as woven cloth (or fired ceramics) had to wait until much later. Well, Lucy, we sure surprised them, didn't we!

[Lucy] Yes we did, Adam.

Well, when you think about it, it's obvious that nothing woven from organic fibers could've survived so long. Nor did stone-age artisans have any way to preserve their poorly-fired clay. Neither ceramics nor cloth leave many traces for us to find. But it's now clear that they've been around much, much longer than we once thought.

Track 9: Inventing Agriculture (4:51): The last epoch of Lucy's and my journey was the Neolithic Era -- the age of New Stone. This period began with agriculture and it ended -- indeed the Stone Age itself ended -- with the first widespread use of metals So the time has come to talk about how we invented agriculture.

To become the builders and makers that we are, we first had to leave hunting and gathering to take up farming. Historian Jacob Bronowski tells a remarkable tale of plant genetics that suggests this change came down to a key flash of human ingenuity.

Archaeological evidence makes it clear that two stages of genetic change set the stage. Something over ten thousand years ago, in the region around Jericho and the Dead Sea, the ancestor of wheat closely resembled a wild grass. It was nothing like the heavy grain-bearing wheat of today. Then a mutation occurred in which this plant was crossed with another grass. The result was a fertile hybrid called emmer, with edible seeds that blew in the wind and sowed themselves.

[Lucy] We lived in that region as a hunter-gathering people called the Natufians. By then, the climate had been warming for two thousand years. The area had been fairly lush. Now it grew arid. Game moved north. The vegetation changed. But the wild grains liked that drier climate. You and I began eating a lot more grain. We did less hunter-gathering, and we took to harvesting. We didn't do any planting yet, because emmer sowed itself.

That's when a remarkable thing happened. A second genetic mutation occurred sometime after ten thousand years ago. This mutation yielded something very close to our modern wheat, with its much plumper grain. It may've happened many times before that, but if it did we had no way of knowing, because wheat doesn't blow in the wind, and it can't sow itself. A mutation -- even a fertile one -- did not survive on its own.

Modern wheat was that fertile mutation of wild wheat. It made much better food. But its seeds didn't go anywhere. They were bound more firmly to the stalk, and they couldn't ride the wind. Without farmers to collect and sow wheat, it dies. Modern wheat created farming by wedding its own survival to that of the farmer.

And your anthropologists come to a great riddle. How did modern wheat replace those wild grains? Isolated mutations died without human help. Were Lucy and I clever enough to recognize and pick out that lone stalk of fat wheat in a field of grain?

And your anthropologists come to a great riddle. How did modern wheat replace those wild grains? Isolated mutations died without human help. Were Lucy and I clever enough to recognize and pick out that lone stalk of fat wheat in a field of grain?

Scientists used to think so. But try another scenario: We Natufians of ten thousand years ago needed much more grain. We could get it by planting some seeds ourselves. Once we did, the fat wheat had its chance. It was easier to harvest. The seeds stayed in place when you cut it. Every time we Natufians harvested seed, we got proportionately more of the mutations. We lost more of the wild grain.

It took only a generation or so of that before a single mutation took over. The result was an unexpected wedding. In no time at all, modern wheat dominated the fields. And that was both a blessing and a curse.

We'd unwittingly replaced the old wild wheat with far richer food. But it was a food that could survive only by their continued intervention. No more lilies of the field. From now on we would live better, but we'd also be forever bound to this wonderful new food by the new technology of agriculture.

What happened in the Holy Land could, of course, happen elsewhere. A similar drama played out in the Americas much later. As the so-called Native Americans, we actually migrated here across the then-Bering-Strait just before the invention of agriculture. Here we had to invent agriculture independently, somewhat later. Anthropologists find evidence of planting and harvesting in the Americas from about four thousand years ago onward. Maize seems to've turned up as a genetic mutation eighteen hundred years ago, just as wheat did ten thousand years ago in the Middle East.

The story of agriculture in Europe is somewhat easier to follow just because the population was more dense and left more tracks. Let's look at that story next.

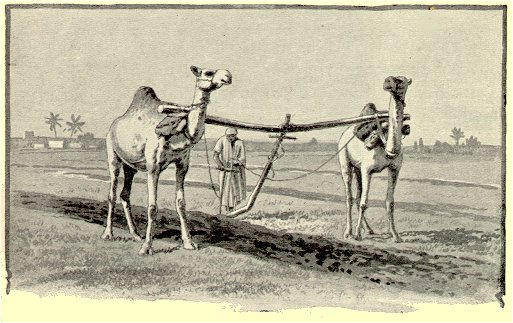

From Stoddard's Lectures, 1897. A stick plow, of ancient design, in use in Egypt.

Track 10: Agriculture in Europe (6:30): It was Fall, 1974. Lucy and I were trudging through the forest along the not-so-blue Danube, under a light drizzle. We walked along Jugoslavia's side of the river. We were on a two-mile walk to an eight-thousand-year-old archaeological site -- the village of Lepenski Vir.

[Lucy] Oh, Adam, I remember that. Overcast and rainy.

Remember that peasant hut and the old woman? She was inside, but she had a rough wooden table and chair out in front, overlooking the river. Do you remember the knife and the pieces of apple on the table? We figured she went out there to sit -- to look at the great river, and think about time and mortality.

[Lucy] We guessed she might be a widow -- lonely.

Half an hour later we reached a small circle of stone huts in the muddy woods. Lepenski Vir was part of the great fuss kicked up by carbon dating. Up to then, prehistory dating had been detective work based on circumstantial evidence. Event B had to fall after A. Event C happened sometime after A, but before B, and so on.

Chronologies didn't have many hard dates to go by. Archaeologists had once dated Lepenski Vir in 2500 B.C. By now, it's retreated to a period between 8400 and 7000 years ago. In 1974, scholars were at each other's throats trying to stem the damage that carbon dating was doing to their textbooks.

I'd better explain how carbon dating works: The cosmic radiation of neutrons converts atoms of nitrogen into the heavy isotope of carbon called carbon-14. First that isotope combines to form high-altitude carbon dioxide. By the time plants and animals take up carbon dioxide, one carbon atom in a trillion is carbon-14.

But carbon-14 is radioactive. Every 5730 years, half of it decays back to regular nitrogen. Measure the fraction of carbon-14 left in any artifact that once lived -- in bone, ash, shell, or grain -- and you can tell how long ago it lived.

To make carbon dating work you have to calibrate it with known dates. We know dates of artifacts from certain Egyptian royalty. The rings of old trees give accurate dates for the wood inside. You might think tree rings couldn't take you back very far. But some California bristle cone pines have lived five thousand years.

At first, carbon dating had tough sledding. We had to make corrections. For one thing, Earth's atmosphere has changed. The amount of carbon-14 in the air five thousand years ago wasn't quite the same as it is today.

As the work went on, old dates moved back into time. Agriculture became two thousand years older than we'd thought. Traditional history suffered the most right here in these rainy woods along the Danube. The people of Lepenski Vir lived in villages, made art, and worshiped the gods of the river long before the Pharaohs.

[Lucy] So we walked along the river, threading through the small farms that break into the forest here and there. The compact and efficient style of farming seemed old as the river itself. You and I didn't realize that day above the Danube that these were the very first northern European farmlands.

After the invention of farming in the Middle East, the Greeks were next to take it up -- about five hundred years later. From there, the path of farming split into two directions. Temperate-zone farming reached Italy 7800 years ago and found its way into Spain and France 7400 years back. That migration, it turns out, took place by sea. Our stone-age ancestors were accomplished sailors and traders long before they learned to farm.

But farming spread even more rapidly up the Greek peninsula, through Macedonia, to the Danube. People had been farming the plateau where we walked that day for eight thousand years. At first, farming settled into the plains of Serbia and Hungary. Much of this movement appears to've been colonization. Farming reached central Europe 7400 years ago, but it didn't get to England and Scandinavia until 1600 years after that.

You can trace that migration in two technologies that followed it. One was the livestock that came out of Turkey and went with the farmers: sheep, goats, cows, and pigs. Even today, diets in that part of the world are rich in roast lamb, beef, and pork.

The other marker was a so-called Linear Pottery Culture that came out of Hungary some 7600 years ago. Throughout the migration, people decorated their pots with scribed lines in the clay. Their farming had to differ radically from that in the dry Mediterranean countries. Mediterranean farmers broke their brittle soil with a stick plow that simply fractured it. Northern farmers had to turn furrows with a much heavier plow. Our word plow comes from an old word, plug, which has no kin in any European language.

Not long ago we discovered the preserved body of a man from one of those farming communities frozen in the Tyrolean Alps -- the so-called ice-man. As we study him, it becomes clear he lived a civilized life. He lived in a house and had some of the first copper implements in that world. He was probably on a trading mission.

So we often go back to that rainy day in 1974 -- to smells of apples, straw, manure -- to the ancient quiet of a peaceful people once living there -- to a steep straw-roofed peasant hut -- to the sense that if we'd suddenly been shifted back eight thousand years, things wouldn't have seemed so different. As we relive that day, we feel our kinship with people who once moved their modest herds into Europe and began forming the world we know today.

[Lucy] On the way out we passed the table again. The woman seemed older when we came back. Now she sat there, eating her apple and gazing out at the river. What were three thousand years more or less, as she honored the one thing no one will ever date -- the timeless dark water moving relentlessly below her.

Track 11: Spreading East and West (6:55): The spread of technology and the spread of people were, of course, one and the same. This all seems to've taken place in Asia by a process of going outward, and then returning.

Physiologist Jared Diamond helps us to see how this worked by leading us on a pilgrimage to Wallace's line. That's an imaginary line separating Borneo and Java from the Celebes and other islands to the southeast. "[Crossing] that line," he says, "may have been what made our ancestors truly human."

Alfred Russel Wallace was the now-almost-forgotten scientist who formulated the theory of evolution by natural selection at the same time Darwin did. Darwin had pretty well finished writing The Origin of Species when he learned that Wallace was about to publish a similar idea. When Wallace heard about Darwin, he did something that we find astonishing today. He politely stood aside and let Darwin publish first.

Among his many contributions, Wallace identified the demarcation between species of southeast Asia and completely different species in Australia and New Guinea. There are other such regions. The Sahara is one. A band from northwest India through the Himalayas and Indochina forms another such zone of separation. But Wallace's line has special importance.

For a long time, you've known that modern humans evolved in Africa a hundred thousand or so years ago, and that they began making dramatic art and tools in Europe thirty or forty thousand years ago. But we've paid scant attention to the world southeast of Wallace's line.

The so-called Java Ape Man fossils make it clear that we ancestors of modern humans reached southeast Asia a million years ago. Java Man got as far as Borneo and Java over land links that existed before the glacial epochs. But those links ended there, and he couldn't get to New Guinea and Australia.

Yet modern humans have occupied Australia for sixty thousand years. Somehow, modern humans appeared in Java Man's world, and they managed to go island-hopping all the way to Australia. There they practiced advanced art and technology that rival what we find in the caves of central Europe. The catch is, they did so much earlier than the European Cro-Magnons.

And so, Jared Diamond observes, we were the one species that lived on both sides of Wallace's line. The crucible of human creativity might well have been Australia. He believes the art and technology of Australian aborigines slowly trickled back and eventually reached Europe. Diamond thinks that crossing Wallace's line was the giant step that made us into a technological species.

Eventually the vast geography and resources of Eurasia allowed the aborigines' cousins to run ahead -- to invent writing and the wheel, to build canons and cathedrals. Eventually, when Dutch and English navigators found their way back to Australia, all they saw were shockingly primitive humans. They had no way to see the sophistication of Aborigine survival strategies. They had no idea they should be saying "Thank you" to those ancient teachers.

But that was all before neolithic advances. Once we had agriculture, the nature of human migration changed. Diamond asks us to consider the odd fact that, of the four large continents, only one runs east and west. It's the largest one, Eurasia, formed by Europe and Asia. Eurasia is nine thousand miles wide. Both the Americas and Africa run north and south. Furthermore, climate largely follows latitude, not longitude. Eurasia is not only the largest of the continents, but it's the only one where you can travel more than three thousand miles without encountering radical changes in the general climate.

That fact has had a powerful influence on human life. The llama never found its way from South America into Central America, nor did the bison move south beyond the present-day United States. Mexican corn couldn't grow in Canada.

In Eurasia, horses and cattle spread to both Spain and China. After agriculture arose in the Middle East, it spread methodically eastward and westward. Not only did domestic plants have lands to move into; the people who grew them also followed the climates they'd learned to tolerate.

That spread did not strictly follow lines of latitude, but it zig-zagged slightly to accommodate climatic variations. We saw, in Track 10, how agriculture found its way through the Balkans and diagonally across Europe. It finally reached the temperate parts of Ireland around 3000 B.C.

The humans who used domesticated animals and agriculture were part and parcel of those technologies. As we moved with our animals and agriculture, our technologies followed. Two particular technologies, virtually unknown in Africa or the Americas, spread laterally in Eurasia. They were writing and the wheel.

The wheel, invented fifty-five hundred years ago at the northern end of the fertile crescent, diffused rapidly across Eurasia. Ancient Mexicans thought of the wheel, but since agriculture didn't move north or south, neither did the wheel. It died in isolation.

Writing, invented fifty-two hundred years ago in Egypt, traveled rapidly throughout Eurasia and across North Africa, but not downward into sub-Saharan Africa. Writing also arose in Central America, but, like the wheel, it stayed there.

So agriculture and domesticated animals came late to the other three large continents, and, once there, they stayed horizontally stratified. Diamond's radical suggestion is that the lateral diffusion of agriculture in Eurasia jump-started all its technologies.

Long ago, Daniel Webster had a visceral understanding of this process. In 1840, just before he became secretary of state, he wrote,

[Lucy] When tillage begins, other arts follow.

The farmers therefore are the founders of civilization.

Now Diamond suggests that early inhabitants were able to give full expression to that natural kinship of agriculture and technology on only one continent -- only in horizontal Eurasia.

Track 12: A Six-thousand Year Old Road (3:40): Here's a pair of numbers to consider. Agriculture reached Europe over seven thousand years ago, yet the Bronze Age and writing didn't get there for another three thousand years. What was life like, in between?

Think about Roman roads. They loom so large in our histories of technology that we can easily miss the fact that the Romans were far from being the first road-builders. Archaeologist John Coles tells about a strange road that was far older. The story begins in 1970, when Raymond Sweet was cleaning drainage ditches in a peat bog near Bristol, England.

Deep in the peat, Sweet struck a wooden plank. It was the wrong thing in the wrong place, so he took it to Coles at Cambridge University. Coles dated it at 4000 B.C. A major dig was begun, and the full meaning of it began to emerge. The trail of wood went on and on, from what had been one island in the fen to another -- over a mile away.

The wood was well preserved. This strange structure had been used for a generation. Then reeds closed in, and peat quickly formed over it. The peat was acidic enough to kill the bacteria that degrade wood. As archaeologists uncovered it, they began to understand the shape of it.

Six thousand years ago, neolithic engineers needed to get back and forth across the swamp below their village. They contrived a long walkway. First they laid a mile-long rail of four-inch-diameter poles on the underwater soil. Then they pounded five-foot pegs into the ground at a 45-degree angle. These pegs criss-crossed over the poles. They formed X-shaped brackets every few feet. The poles carried their weight. Finally wide planks had been fitted into the upper arms of the X. The planks formed a walkway a foot above the water.

It was quite a piece of work for people still in the Stone Age. The children of these engineers would build Stonehenge nearby, but not for another two thousand years. Tool-marks on the wood show a fine command of carpentry. These boards were formed by people with better tools than we would have guessed. It took a very sophisticated wood-splitting technique to make those planks. The excavation even turned up surveyor's stakes that'd been used to lay out the path for its builders.

There's more. Artifacts dropped along the walkway show that these not-so-primitive people made pottery, that they'd invented glue, and that they traded with distant tribes for flint.

[Lucy] The most startling artifact was that axe head shaped from European jade. Time forgot us when we lived in that village near Bristol, but we clearly owned some knowledge that will remain mysterious.

And yet, this path reveals much more than it hides. It tells about social cohesion. These ancestors could put their wills and minds together and produce a huge unique project for the common good. So it was all there, six thousand years ago -- all the earmarks of an agricultural society. Here was a high level of social organization, a strongly developed technology, and both the skill and imagination to dream up, and execute, a major engineering feat.

In a world based on biodegradable wood, projects like this were made over and over and then lost. But we were making many such things. Our skills were becoming formidable.

Track 13: The Great Pyramid and the High Stone Age (6:07): By 5500 years ago, we were on the verge of making the three great breakthroughs that would end Lucy's and my odyssey through the Stone Age. Three truly wondrous inventions, and our Stone Age would be no more.

[Lucy] We could've hung on after they thought up the wheel and began using metals. Writing was what ended our journey through the Stone Age.

The odd thing is that the wheel and metal-using turned up just around the same time writing did. The wheel came out of the Fertile Crescent in about 3500 B.C. By then, the Egyptians and others had just started working stray lumps of alluvial copper and silver. But the invention of rudimentary hieroglyphic writing was what really changed the game 5500 hundred years ago.

And now that we had writing -- now that we had a written record -- who do you suppose the first person in history was.

[Lucy] Why Adam, how odd you should ask.

No, no. We're talking about writing here. Historian Will Durant offers Imhotep as the first real person to turn up in the historical record. Before that we have only cardboard figures -- legendary kings and patriarchs. So let's meet this Adam of recorded history.

Imhotep was the advisor to the Egyptian King Zoser. Zoser ruled soon after 2700 B.C. He was the dominant king of the third dynasty and the first ruler of what we call the Old Kingdom. The Old Kingdom was the beginning of the ancient Egypt we read about. Because Egypt had recently invented writing, it was now possible to tell us about her works. Her heroic stone structures began under Zoser. The Great Pyramid would go up just a few centuries later.

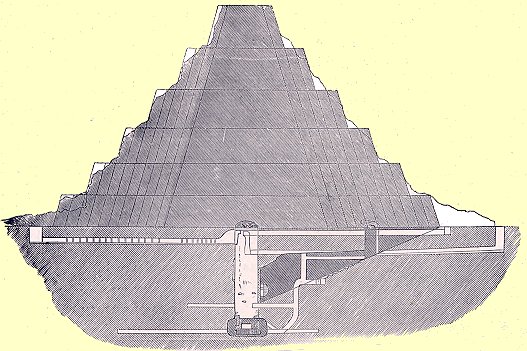

The force behind all that was not Zoser, but Imhotep. Imhotep created a new architectural order. He designed the Stepped Pyramid at Saqqara. That was the first great Egyptian pyramid. It's the oldest of those architectural treasures that still stand today. It rose like a great wedding cake, surrounded by a delicate low-lying limestone temple that covered 300 by 600 yards of the ground around it.

The Stepped Pyramid at Saqqara

(from A History of Architecture in All Countries, 1893)

But architecture was only a part of Imhotep's legacy. He was also a writer and a poet. And Egypt honored him less for writing or building than for his medicine. Here the water gets muddy. For, unlike his architecture, we have no idea what Imhotep contributed to medicine. What we do know is, the Egyptians eventually deified him for his healing. By the 6th century B.C., Imhotep had displaced the god Toth as the god of healing. He was even called the son of the god Ptah.

By then, the Greeks had their own god of healing, Asclepios. And, it turns out, Asclepios was also derived from a real person. Homer mentioned him in the Iliad only as a fine physician. But, as Asclepios was deified, he too was given a god for a father -- in this case, Apollo. Finally, Imhotep and Asclepios appear as a single god called Asclepios-Imhoutes. I guess you'd call that hedging your bets.

So, although Imhotep began as the first person in recorded history; he was forgotten as a human being. He was reduced to a mere god, and history is the worse for that. Still, history now existed, and it hadn't existed before. Emerson would eventually be able to write, "There is properly no History; only Biography." From now on, we would have history and we would have biography. Imhotep stood only on the threshold of history. Even though we know his name, the only real biography we have for Imhotep are those glorious architectural remains at Saqqara.

From now on, Lucy and I would be replaced by real people with real names. But our Stone Age had one last wonder to give to you. It was the Great Pyramid of Khufu, at Giza. The age of bronze and the age of writing were well upon us by 2560 B.C., which is roughly when it was finished. But much great technology reaches its apogee just after its time has passed.

Howard Hughes' huge flying boat, the Hughes Hercules (better know as the Spruce Goose) was such a machine. The Empire State Building was the last great skyscraper just after the automobile made it clear that huge buildings were not the way the urban landscape was being shaped in 1931. Not until after ground was broken for the World Trade Center in 1966 would anything taller be built. The height of the Great Pyramid, built with Stone Age technology, was 480 feet. That wouldn't be exceeded until the Washington Monument was finished in 1885. Of the Seven Wonders of the Classical World the Great Pyramid is both the oldest by far, and it's the only one that still stands today. And, Lucy, I think you and I have the right to claim it for the Stone Age.

[Lucy] We certainly do!

There's much more to tell about the Stone Age. We haven't mentioned successful Stone Age house-building, sailing vessels, and even brain surgery. But the Great Pyramid is a good place to stop. Lucy and I need to shed our ectoplasm and fade back into the mists of unrecorded history. Just remember, the next time you feel your creative juices are not running fully, that we hominids have been creators of fine technology since long before anyone held pen in hand to tell of it. And that part of our legacy is still yours to claim -- any time.

[Lucy] We're Lucy and Adam, from the University of Houston, where you'll find modern hominids, interested in the way inventive minds work.

Track 14: Data This is where the data are stored for the CD-ROM. Please ignore it here as well as on your audio CD player.

[Total time: 59:03 minutes]

A FEW SOURCES

Track 2:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 1050.

Falk, D., Braindance: New Discoveries About Human Origins and Brain Evolution. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1992.

Track 3:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 1109.

Schick, K.D., and Toth, N., Making Silent Stones Speak: Human Evolution and the Dawn of Technology. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1993.

Track 4:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 775.

Calvin, W.H., The Throwing Madonna: Essays on the Brain. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1983, Part I, Ethnology and Evolution.

Track 5:

Much of this Track was derived from Engines Episode 307.

Kerisel, J., Down to Earth. Boston: A.A. Balkema, 1987, Chapter 1.

You will find a great deal of information about the Zhoukoudian Cave on the web. It, like the field of archaeology in general, is in a high state of flux as new data are accumulated.

Track 6:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 1232.

The Shakespearean conversation takes place between Lorenzo and Jessica in The Merchant of Venice, Act V, Scene 1.

Stevens, W., The Man with the Blue Guitar. The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens, New York: Albert A. Knopf, 1982. This episode has been greatly revised as Episode 1559.

Early Music. Editorial sidebar in Science, Vol. 276, 11 April, 1997, pg. 205.

Fink, Bob, NEANDERTHAL FLUTE: Oldest Known Musical Instrument Plays Notes of Do, Re, Mi, Scale. Available on the Internet at http://www.webster.sk.ca/greenwich/fl-compl.htm.

Track 7:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 359.

Vandiver, P.B., Soffer, O., Klima, B., and Svoboda, J., The Origins of Ceramic Technology at Dolni Vestonice, Czechoslovakia. Science, Vol. 246, Nov. 24, 1989, pp. 1002-1008.

White, R., The Upper Paleolithic: A Human Revolution. 1989 Yearbook of Science and the Future (D. Calhoun et al., eds.). Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., 1988, pp. 30-49.

Science magazine (Vol. 268, April 28, 1995) includes several articles related to redating paleolithic technologies.

Track 8:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episodes 840 and 1024.

Wilford, J. N., Site in Turkey Yields Oldest Cloth Ever Found. New York Times, Science Times, Tue., July 13, 1993, pp. B5, B8.

Barber, E.J.W., The Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages, with Special Reference to the Aegean. Princeton, NJ: the Princeton University Press, 1991.

Crowfoot, G.M., Textiles, Basketry, and Mats. A History of Technology, Vol. I (C. Singer, E.J. Holmyard, and A.R. Hall, eds.). New York: Oxford University Press, 1954, Chapter 16.

Fowler, B., Find Suggests Weaving Preceded Settled Life. Science Times, The New York Times, Tuesday, May 9, 1995, pp. B7-B8.

Track 9:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episodes 540 and 20 and 571.

Stevens, W., Dry Climate May Have Forced Invention of Agriculture. New York Times, SCIENCE, Tuesday, April 2, 1991, Section B.

Bronowski, J., The Harvest of the Seasons. The Ascent of Man, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1973, Chapter 2.

Smith, B.D., Harvest of Prehistory. The Sciences, May/June, 1991, pp. 30-35.

Track 10:

This Track was derived largely Engines Episodes 776 and 1121.

Renfrew, C., Before Civilization: The Radiocarbon Revolution and Prehistoric Europe. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1973.

Bogucki, P., The Spread of Early Farming in Europe. American Scientist, Vol. 84, No. 3, May-June, 1996, pp. 242-253.

Track 11:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 1270.

Diamond, J., Mr. Wallace's Line. Discover, August, 1997, pp. 76-83.

Diamond, J., Spacious Skies and Tilted Axes. Guns, Germs, and Steel, W.W. Norton & Company, 1999, pp. 176-191.

Track 12:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 343.

Coles, J.M., The World's Oldest Road. Scientific American, November 1989, pp. 100-106.

Track 13:

This Track was derived largely from Engines Episode 1074.

Durant, W., The Story of Civilization. Part I: Our Oriental Heritage. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1954. See especially p. 147.

Casson, L., Ancient Egypt. New York: Time, Inc., 1965.

See also the Encyclopaedia Britannica article on Egypt.