s we meet these ghosts from every walk of life – rich and poor, famous and forgotten – I think about a wonderful passage in the Book of Ecclesiasticus. It begins,

s we meet these ghosts from every walk of life – rich and poor, famous and forgotten – I think about a wonderful passage in the Book of Ecclesiasticus. It begins,

Let us now praise famous men, ...

Such as did bear rule in their kingdoms,

Men renowned for their power, ...

Such as found out musical tunes,

And recited verses in writing:

All these were honoured in their generations,...

But the text moves on to this far more realistic – even poignant – understanding of invention. It says:

And some there be, which have no memorial;

Who are perished as though they had never been.

Their bodies are buried in peace;

But their name lives for evermore. ...

The people shall tell of their wisdom.

We cannot study the history of technology long before we find ourselves haunted by countless people with no memorial who do, nevertheless, live forever – anonymous inventors of the wheel, the windmill, the plow. Some of the ghosts in these books have names. Some were even renowned in their time. Some did much, some little, but all shaped us toward whatever we are today.

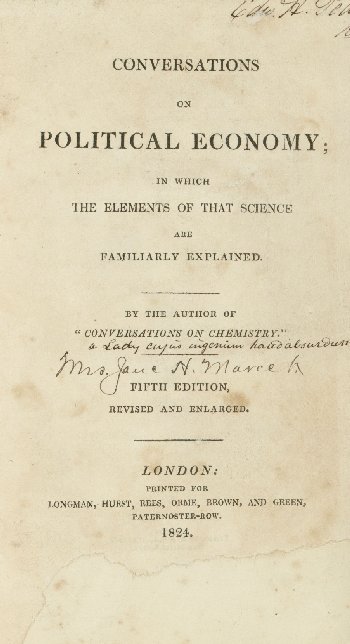

Here's a case in point – a ghost without a name, or at least not a full name. In fact, the ghost in this book is less the owner than it is the age he represents. The book is an 1824 edition of Jane Marcet's Conversations on Political Economy. It was rebound after the first owner had signed it. When the bookbinder squared off the pages, he trimmed the name. All we can make out is Edward or Edwin H..

Here's a case in point – a ghost without a name, or at least not a full name. In fact, the ghost in this book is less the owner than it is the age he represents. The book is an 1824 edition of Jane Marcet's Conversations on Political Economy. It was rebound after the first owner had signed it. When the bookbinder squared off the pages, he trimmed the name. All we can make out is Edward or Edwin H..

Marcet's name is not there either. Since it was unseemly for a woman to be named as the author, we read only By the author of Conversations in Chemistry. Not until her 13th edition of this book, did Marcet's own name appear on the title page. The owner, however, has identified her and he's written on the title page – part in Latin, part in English: "a Lady cujus ingenium haud absurdum, Mrs. Jane H. Marcet."

What did that mean? A librarian with a background in classics came to my aid. It literally means "a lady whose talent is by no means" – what? "awkward?" "absurd?" It's hard to know what the book's owner meant by the word "absurdum" without some context. It turns out that he'd paraphrased a line from the Roman author Sallust. Sallust tells about a woman named Sempronia.

Now among these women was Sempronia, who had often committed many crimes of masculine daring ... able to play the lyre and dance more skillfully than an honest woman ... there was nothing she held so cheap as modesty and chastity ...

And that's followed by a free translation of the line on the title page:

She was a woman of no mean endowments.

Is this how the owner saw Marcet? Brilliant, iconoclastic, half-courtesan? Then I realize that the majority of Marcet's books – these instructional books for young ladies – were owned and read by men. This one is filled with marginal notes – all down-to-earth and factual. Every few paragraphs Edw. H. has written a little marginal summary. He obviously took the book very seriously.

Yet that strange quotation from Sallust! There can be no doubt that Edw. H. meant to celebrate the breakthrough that Marcet had made in a rigid society. Yet he ties into early-19th-century apprehensions even as Marcet herself does. Remember, in Track 3, how she wrote, "In venturing to offer to the public ... an Introduction to Chemistry, the author, herself a woman, ... feels it ... necessary to apologize ... "

Women have been telling us how they've been written out of history. Now we stumble into the middle of that process. Everyone is bothered by Marcet's gender. Edw. H., society in general, even Marcet herself. Everyone tries to find ways to deal with the truth of Marcet's enormous educational impact. Marcet was one of the great technical educators two centuries ago and Edw. H. summons up a disturbing spectre of her world when he has to cast her as wanton before he can praise her for all she's done. Ghosts of many kinds lurk in these old pages, and this truly is a ghost of some Christmas past.

Anonymous, The Book of Ecclesiasticus. Chapter 44. This is a part of the Apocrypha in the King James Bible. The Catholic Vulgate Bible assigns it the somewhat higher status of a deuterocanonical book.

J. H. Marcet, Conversations on Political Economy... , 5th ed. (London: Longman etc., 1824). My thanks to Special Collections, University of Houston Libraries for the scan of the title page of this particular copy.

Sallust. Sallust with an English Translation. (tr. by J.C. Rolfe). The Loeb Classical Library, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1921. I am most grateful to Dr. Jeff Fadell at the University of Houston Library for his fine detective work in tracking down the Latin quotation.