Today, we talk about streamlining. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The watchword of the 1930s was modern. If I knew one thing as a child, it was that I lived in the modern world. It was a world where the vertical lines of art deco were giving way to horizontal streamlined forms. Everything in the 30s, 40s, and 50s was streamlined. The Douglas DC-3 had brought streamlining to passenger airplanes. The Chrysler "Airflow" and the Lincoln "Zephyr" brought it to the automobile. Even my first bike was streamlined.

Earlier in the 20th century, the great German experts in fluid flow had shown us how to streamline bodies to reduce wind resistance. It certainly served this function when things moved fast. But my bicycle hardly qualified. Nor did the streamlined Microchef kitchen stove that came out in 1930. Bathrooms were streamlined. Tractors were streamlined. Streamlining was a metaphor for the brave new world we all lived in.

A confusion of design schools competed with each other in the early '30s. The German Bauhaus school had been scattered by the Nazis. Art deco was dying. Neither the classic-colonials nor Le Corbusier and the International School could gain ascendancy.

Then streamlining came out of this gaggle, propelled by American industry and making its simple appeal to the child in all of us. It certainly appealed to the child I was then. In reality, streamlining was a sales gimmick -- something to distract us from the tawdry realities of the depression. It told us to buy things. It told us we could all go fast. It was hardly one of the great humanist schools of design.

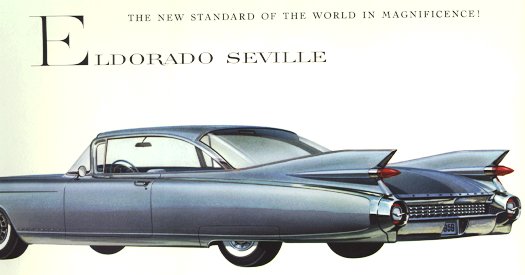

The Nazis and Bolsheviks used streamlining as a propaganda tool. American industry used it to make us into consumers. It fairly smelled of technocracy. It lasted 'til the 1950s, when, at last, we were all offended by its dying excesses -- the enormous tailfins and chromium structures that made the automobile ridiculous by any esthetic standard.

But I loved airplanes as a child, and the functional curved aeroform shape touched something in me. The way the gentle camber of an airfoil gave the invisible wind a handle by which to pluck a 50-ton airplane into the sky -- that was truly magical.

"When I was a child," said St. Paul, "I thought as a child." Streamlining was a childish symbol of our modern world -- now put away with other childish things. But I still sneak an occasional look back at that vision of motion, speed, and buoyancy.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

More on the streamlining movement can be found in an exhibit review: Hyde, C.K., 'Streamlining America,' An Exhibit at the Henry Ford Museum. Dearborn, Michigan, Technology and Culture, Vol. 29, No. 1, 1988, pp. 125-129, or in the exhibit itself.

This episode has been greatly revised as Episode 1480.

(From an expensive Cadillac mailout brochure, with permission of Bill Howell)

The 1959 Cadillac Eldarado Seville