Today, we stick a little yellow footnote on a story of invention. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Post-it notes have been commonplace since around 1980. All the nicest, and the most upsetting, things I get in the mail are written on those little yellow bits of sticky paper. They bring a human voice to office formality.

Post-its are the product of three stages of invention. The first stage took place when a 3-M chemist named Spence Silver played with polymer cements. I say played because 3-M asks its technical people to spend 15 percent of their time trying out new -- even useless -- ideas. Silver mixed up a batch of glue that violated all the normal rules of mixing.

And he got a glue that was wrong in every way. It wasn't very sticky, and it would never dry. When you pulled glued papers apart, all the glue stuck either to one paper or the other. It was a useless product -- or was it?

Silver came up with one use. He covered a bulletin board with the glue. You could slap on a piece of paper -- then peel it off later. Nice idea, but nothing anyone really needed.

Now enter Arthur Fry -- 3-M chemist, mechanic, and choir director. He knew about Silver's new glue, and he needed a simple way to mark his hymnal. One Sunday, his mind on the service, it hit him. With sticky slips of paper he could temporarily attach markers to the hymnal. And so the Post-it was born.

First 3-M made Post-it pads and distributed them in the company. They were wildly popular. 3-M had a winner. But when they tried to market Post-it pads in Richmond, Virginia, they bombed. Who'd pay a dollar for a pack of tiny note-papers?

And here we read the oldest lesson in new technologies. It is that the technology itself must teach its use to people. And this wasn't just a better glue or a better paper clip. Rather, it was a whole new concept. It was alien to anyone's experience.

Post-it notes were about to go the way of miniature TVs. Then two 3-M marketers made a last try. They went door to door -- first in Richmond, then in Boise. They didn't sell Post-it pads. They gave them away to businesses. Now they had buyers. They addicted every office they went into.

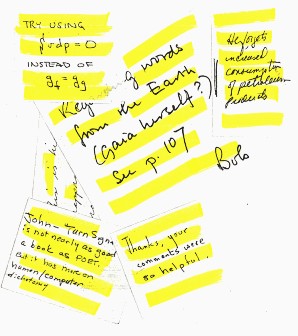

So the three parts in this inventive process were play, reverie, and teaching. Silver created the adhesive by playing around -- by breaking his own rules as a chemist. Fry simply let the question of use ride in an idle corner of his mind until it bore fruit. And finally, two marketers let Post-its teach their use to us -- we, who didn't know how badly we needed them.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Nayak, P.R., and Ketteringham, J.M., Breakthroughs: How the Vision and Drive of Innovators in Sixteen Companies Created Commercial Breakthroughs that Swept the World. New York: Rawson Associates, 1986, Chapter 3.

My thanks to Judy Myers, UH Library, for calling the Post-it story to my attention and providing the source material.