Today, we'll ride on a cable car. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Cable cars symbolize San Francisco just as powerfully as the Eiffel Tower symbolizes Paris. And rightly so! Where else have you ever seen anything quite like them?

Cable cars were the clever answer to a problem. In 1870 neither electricity nor internal combustion engines were in general use. The only obvious way to power a streetcar was with horses or steam engines. You could hardly put a fleet of mini-steam locomotives on city streets. And that seemed to leave only horses.

But then, in 1869, Andrew Hallidie visited San Francisco. He watched four horses pulling a streetcar up one of the city's murderous hills. One of them slipped and went down. That started a chain reaction. The rest of the horses fell, and the car rolled down the hill dragging the panicked beasts behind it.

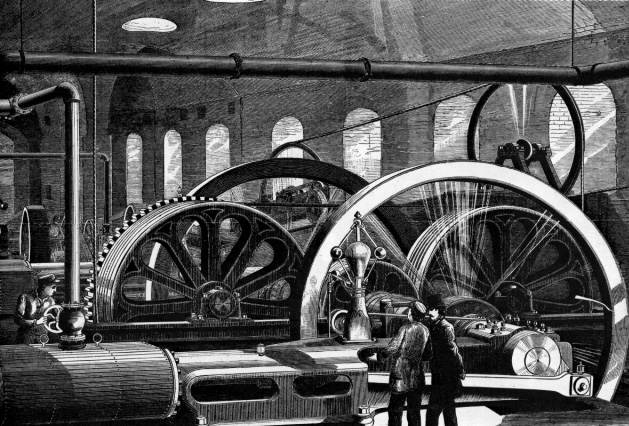

Hallidie was a wire-rope salesman, and he saw an alternative. You could cut a slot in the street and run a moving wire cable through it. You could use a stationary steam engine to drive a moving cable. Then streetcars could be equipped with a mechanism that dropped down into the slot to grasp the cable.

The idea wasn't entirely new. Something like it had been tried in London and again in New Orleans. But Hallidie organized a company; he solved the thorny problem of making a really good quick-release mechanism to grip the cable; and his new system made its debut on precipitous Clay Street in 1873. It wasn't long before 600 streetcars were riding a network of 1¼-inch cables. The length of some cables reached four miles, and they towed streetcars all over San Francisco at a steady 9 mph.

The cable car system quickly spread all over America. But the timing was bad. Edison and Westinghouse were just coming out with electric motors and public electric-supply systems. By 1890 -- in the blink of an eye -- cable cars were made obsolete by the electric streetcar.

Most of the San Francisco cable lines were also abandoned. But what originally drove Hallidie to make those doughty little vehicles was their special talent for scaling San Francisco's seemingly vertical hills. So a few cable lines survived -- survived the earthquake -- survived the fire -- and they're still running. Of course, the system has shrunk. It had 110 miles of track in its heyday. Now it has less than 11 miles.

But what remains is a brief piece of Americana -- frozen in time. The cable cars are sustained by sentiment, of course, but they also survive because they were the right technology in the right place.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

National Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmarks (R.S. Hartenberg, ed.). New York: American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 1979.

Representation of the steam engine system for driving the cable

Probably from the San Francisco station (clipart, source unknown)