The Centennial Exhibition

Today, some thoughts about Cyrus McCormick and America's Centennial. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

We finished our first hundred years sleek, confident, and well-fed. So we ordered a grand birthday party -- the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial. It was the largest exhibition ever mounted -- 236 acres, 30,000 exhibits, and over 8,000,000 visitors.

The Centennial celebrated American industrial power. Its most famous exhibit was the gigantic 1600-HP Corliss steam engine that powered Machinery Hall. The first piece of the Statue of Liberty -- the hand and torch -- had just arrived from France and was put on exhibit. But it paled against the machinery -- the fruit of American factories, the raw muscle of our industries.

The glimpse behind all this wasn't entirely pretty. By 1876 men like Cornelius Vanderbilt, Jay Gould, and Daniel Drew were law unto themselves. They operated above the law and controlled small private armies. The financier Drew loudly complained that America had become "too democratic." In fact, government of and by the people had grown weak, and business was in the saddle.

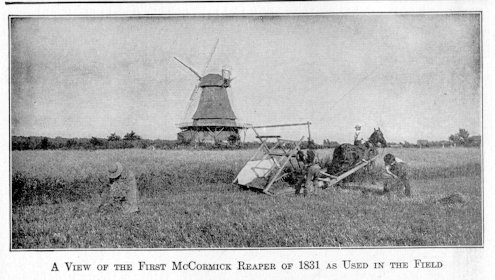

Invention was the specie behind all the machinery. But invention profited the strong -- not necessarily the inventive. Take Cyrus McCormick, for example. He demonstrated his famous reaper in 1831. Then he improved it for two decades. But after he went into production, his life work changed from invention to combat.

Invention was the specie behind all the machinery. But invention profited the strong -- not necessarily the inventive. Take Cyrus McCormick, for example. He demonstrated his famous reaper in 1831. Then he improved it for two decades. But after he went into production, his life work changed from invention to combat.

The patent protection system was also weak. Tough people fought endlessly in the courts for the ownership of ideas. On the way to becoming a millionaire, McCormick retained a young lawyer named Abraham Lincoln to help him ruin just one of his rivals. McCormick simply loved to fight. In 1862 he was overcharged $8.40 for his wife's train luggage. His legal war with the New York Central Railroad ended only when his estate was awarded a $20,000 settlement after his death. His wife wrote to their son, "You see, your dear father's course from first to last is ... vindicated." Nothing about what he'd accomplished by developing the reaper -- only that he'd won an obsessive legal battle.

The great 1876 Centennial subtly celebrated this mentality. By then the individualism that'd brought us so far had gone quite mad. During the next century we've tried, with varying success, to put a leash around the power brokers.

It's been suggested that McCormick took his ideas for the reaper from the slave who helped him build it. But I think the story is even sadder than that. I see a man putting youthful inventiveness behind him. I see McCormick and others forgetting the joyful creativity that'd brought America so far in her first hundred years.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Wilson, M., American Science and Invention: A Pictorial History. New York: Bonanza Books, 1960, pp. 212-221.

From the 1923 Book of World Knowledge