Today, the seed of an invention takes 37 years to sprout. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

A 25-year-old German cavalry officer -- a Prussian nobleman -- came to America during the Civil War as a foreign observer of the Union Army. When I tell you his name you'll all know it, but let's wait a moment for that revelation. In any event, the fellow had quite an adventure here. He narrowly escaped capture by the Confederate Army in Virginia. He watched draft riots in New York, he flirted with young ladies on a Great Lakes boat from Cleveland, Ohio, to Superior, Wisconsin. He ate muskrat and hunted with Indians. His remarkable journey eventually brought him to the International Hotel in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Just across the street from his hotel, a balloonist named John Steiner was flying passengers in his observation balloon. Steiner had flown for the Union Army as a civilian observer. His work probably saved McClellan's Army from defeat in 1862. But he'd quit the Army in a dispute over pay and gone barnstorming.

The German officer decided to add a balloon ride to his American adventure. So Steiner sent him up on a solo flight at the end of a 700-foot tether rope. Our young officer wrote a letter-report of the experience. Outwardly it was straightforward reporting of the military potential of observation balloons; but between the lines bubbled a barely controlled excitement.

The young man returned to Germany and completed a long military career before he came back to this bright moment in his youth. By then, many people had built rigid navigable balloons -- or dirigibles. The first successful one had been flown by the Frenchman Giffard eleven years before that flight in St Paul. But no one had yet made a commercially viable dirigible.

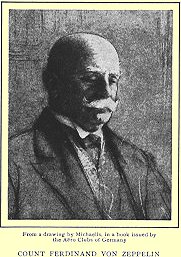

Now our German officer, whose name was Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, took up dirigible-building just after his 60th birthday. He flew his first airship in 1900.

Zeppelin managed to synthesize the various elements other inventors had played with all through the 19th century. He lived and worked for another 14 years, and by the time he died he'd created the grandest machines in the air. The spectacular Zeppelin airships continued to dazzle everyone until the whole technology went up in smoke with the Hindenburg crash in 1937.

And we're left with the astounding fact that the seed for all this was sown in Western America during the Civil War. Shortly before he died, Zeppelin wrote,

While I was above St. Paul I had my first idea of aerial navigation strongly impressed on me and it was there that the first idea of my Zeppelins came to me.

Perhaps Zeppelin was so successful just because he was fulfilling a dream that had grown within him for a whole lifetime.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Crouch, T.D., The Eagle Aloft: Two Centuries of the Balloon in America. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1983.

This episode has been considerably revised as Episode 1682.

From the Century Magazine, 1910